Barbarians and Real Champs

David O’Leary is most likely the best winemaker in Australia you’ve never heard of. He has worked with many great winemakers such as Brian Barry, Mick Knappstein, John Vickery, Bryan Dolan, Jeff Merrill, Brian Croser, Tony Jordan, Chris Hatcher, Wolf Blass and John Glaetzer who won all those Jimmy Watson trophies for his master.

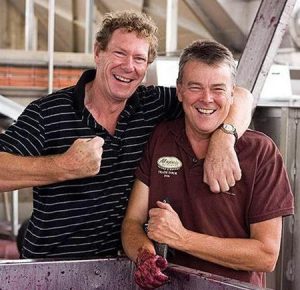

At the turn of the millennium, David and Nick Walker joined forces and set up their own wine company – O’Leary Walker.

At the turn of the millennium, David and Nick Walker joined forces and set up their own wine company – O’Leary Walker.

They had been good friends ever since they met at Roseworthy in the mid-seventies. Between them, David tells me, they have 93 vitages under their belts.

Both worked for several big wine companies, winning some 300 gold medals and 60 trophies for them. It was time to stand out on their own.

The Clare Valley is famous for its Rieslings, which overshadow the great reds made in the area. At my age, I’m reluctant to buy green bananas, let along reds that will hit their drinking sweet spot a decade from now. I made an exception when I tasted a red last year that showed just how underrated Clare reds have been: O’Leary Walker Polish Hill River Armagh Shiraz 2018.

2018 was a warm, low yielding vintage that produced rich, ripe reds of great power. The fruit came from Polish Hill River and Armagh just north of Clare, and David took full advantage of its quality, storing the wine in French oak (25% new) for 2 years. The result is a perfect Clare red that sold for pennies – $20 a bottle.

That’s the genius of David O’Leary: making stunning reds we can afford. Penfolds would charge $100 for a wine of this caliber. It scored 97 points with several reviewers, which is a close to perfect score.

A Wild Time

When I talked with David, he mentioned that he’d been working nightshift during the last few weeks. Years ago, winemakers learnt that the fruit was in better condition when harvested in the cool of the night, but it had to be crushed and processed straight away – therefore the nightshift.

‘Don’t you get tired of working nightshift?’ I asked him, ‘and don’t you have young guys on your team to do that?’

‘Yes we do,’ he answered, ‘but they’re still learning so Nick and I are there to support them.’ He chuckled. ‘Anyway, I quite enjoy nightshift. Had some lunch today, then a quick snooze, and I’m ready to go again.’

David must be on the wrong side of sixty, so you’ve got to admire his energy, and his enthusiasm. He lived through a tumultuous time in Australia’s wine industry: a time when corporate Apex predators ruled the land, gobbling up everything in their way, and sometimes each other.

The story begins with Walter Reynell & Sons falling into the smoke-stained hands of Rothmans of Pall Mall in the 1970s.

In this decade, David O’Leary started work at the Stanley Wine Company, as a lab assistant to Brian Barry. Barry had come from the Riverland co-op Berri-Renmano, where he had raised the quality of the wines to stellar levels. While working with Brian Barry and Mick Knappstein at Stanley, David fell in love with Clare Valley Rieslings, but it was to take many years before the Clare Valley became his home.

In this decade, David O’Leary started work at the Stanley Wine Company, as a lab assistant to Brian Barry. Barry had come from the Riverland co-op Berri-Renmano, where he had raised the quality of the wines to stellar levels. While working with Brian Barry and Mick Knappstein at Stanley, David fell in love with Clare Valley Rieslings, but it was to take many years before the Clare Valley became his home.

The Big Time

David went on to work for Petaluma, where Tony Jordan had set up a contract winemaking service. David did short stints at Heemskerk in Tasmania, then at Lindemans in Coonawarra. Riesling Meister John Vickery had been sent there in 1980 to take charge of the reds – the Rouge Homme range and the Coonawarra trio – the St George twins and Pyrus, the Bordeaux blend.

1982 was David’s practice year for his graduation from Roseworthy Agricultural College. Vickery was famous for his obsession with cleanliness in the winery, and David tells the story of a Miller Drainer he was told to clean. ‘When John inspected it,’ David recalls, ‘he wasn’t happy because he found a couple of pips that I’d missed.’

John Vickery was just one of many great winemakers David O’Leary learnt from. He joined Chateau Reynella just before Hardy’s bought the winery in 1982 – Thomas Hardy had worked there 130 years earlier.

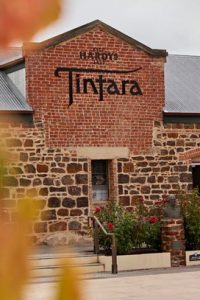

Over the following years, David worked his way up to chief red winemaker, while Hardy’s grew into the largest wine company down under. It owned long established brands such as Tintara, Leasingham and Houghton, and was busy planting new vineyards from Padthaway to Canberra.

Tomorrow The World

This was the time when Australian wine exports boomed, and when the Brits and the Yanks learnt to love the ‘sunshine in a bottle’ wines from down under. These wines never made any money for their makers, but they put Australia on the map.

This was the time when Australian wine exports boomed, and when the Brits and the Yanks learnt to love the ‘sunshine in a bottle’ wines from down under. These wines never made any money for their makers, but they put Australia on the map.

David worked both ends of the quality spectrum, making Eileen Hardy Shiraz and Reynella Cabernet at the top end, and some high volume reds at the bottom end. I suggested that he was one of the last great blenders, and he said: ‘at Hardy’s we had a huge choice of fruit from different regions, and from new vineyards coming on stream, and we used open fermenters and small oak – you couldn’t go wrong!’

David is nothing if not self effacing, I discovered, always giving others credit for his achievements. Chris Shanahan was surprised by the quality of the Nottage Hill Cabernet, ‘a product of the great Padthaway vineyard combined with O’Leary’s genius and enhanced by the open fermenters and oak barrels available only because he also makes the likes of Eileen Hardy and the Chateau Reynella reds.’

By the end of the eighties, David was at the top of his game, and became chief winemaker at Hardy’s. He said, ‘They were the biggest wine company at the time, but their biggest sellers were white wines – Siegersdorf Riesling, Old Castle Riesling, Hardy collection Chardonnay and more.

‘The reds weren’t doing as well,’ David added, ‘but winning the Jimmy Watson trophy in 1988 changed that. It was big win for Hardy’s, and they had the sales and marketing people to take advantage of it, people like David Woods who took sales to another level.’

By the start of the new millennium, BRL Hardy was making one in every 5 bottles of wine down under. Back in the nineties, David was named ‘international red winemaker of the year’ by the International Wine Challenge (IWC).

Sturm Und Drang

Selling Aussie wines oversees was an exciting adventure, but soon some of our movers and shakers fell for the idea of buying a chateau or two in France. Len Evans was at the forefront of this trend, and the late Jim Hardy followed, collecting vineyards in Tuscany, Sicily, France and Chile. North America was to be next but the debts began to pile up and put a stop to Hardy’s hubris.

‘The deregulation of our banking system in the 1980s led to a period of speculative madness by bankers and borrowers,’ industry veteran David Farmer wrote, ‘… a few poor business decisions by the Hardy’s board heralded the end …’

Hardy’s was a wine company with 125 year history, and now it needed a partner to bail it out. The huge Berri-Renmano co-op (nickname: the oil refinery) was the successful suitor, so a shotgun marriage followed. ‘Blue bloods trying to be nice to farmers from the Murray,’ David Farmer wrote, ‘and how humiliating this must have been for the sailing hero Jim Hardy.’

Hardy’s was a wine company with 125 year history, and now it needed a partner to bail it out. The huge Berri-Renmano co-op (nickname: the oil refinery) was the successful suitor, so a shotgun marriage followed. ‘Blue bloods trying to be nice to farmers from the Murray,’ David Farmer wrote, ‘and how humiliating this must have been for the sailing hero Jim Hardy.’

The new entity was called BRL Hardy, and David O’Leary became senior winemaker for the group. He kept his head down and made lots more great reds at Hardy’s Tintara winery in McLaren Vale, despite the post-merger upheaval. More here from Chris Shanahan.

Briefly he also became one of our many flying winemakers, making wine for Hardy’s in France and California. David was philosophical about the outfall from the merger. ‘It’s sad to see good people pushed out of companies,’ he said, ‘good people who’ve worked for them all their lives. We saw it at Penfolds too, in the late nineties, lots of good people laid off.’

David also made the point that you never left a good job in those days, but in 1994 he turned his back on Hardy’s and joined Mildara Blass. Once again, David harbours no ill feelings, and just talked about all the great people he had worked with at Hardy’s: ‘Geoff Weaver, Tim James, Tom Newton, Wayne Jackson, Brian Dolan, Mark Tummel and of course Sir James Hardy and all the Hardys.’

Constellation Brands bought BRL Hardy’s a few years later for $1.3 billion, followed by Southcorp paying $1.5 billion for Rosemount. Aussie wine had been fully corporatised.

Black Opal

Mildara Blass was run by Ray King, one of the few CEOs who generated handsome profits for shareholders of an Aussie wine company at that time. King’s focus was on producing good reds at sharp prices, and David had proven that he was as good as they come in that genre.

Ray King had acquired a bunch of wineries over the years that included Wolf Blass, Maglieri, Yellowglen, Rothbury Estate, Saltram, Bailey’s, Ingoldby and St Huberts. Years earlier, Wolf Blass had bought the big, beautiful Quelltaler property in the Clare Valley from Cognac maker Remy Martin and renamed it Eaglehawk, and later on Black Opal.

King changed the name to Annie’s Lane, and the new focus was on a range of $15 wines. David O’Leary was the guiding light once again, and I remember how good the reds and Rieslings were for the money in the late nineties.

‘Annie’s Lane was a terrific experience,’ says David. ‘After 14 years with Hardy’s, I met and worked with great people from the Barossa to the Riverland. Ray King was on top of his game, Mike Press was chief winemaker and had talented people in the Group like Chris Hatcher and John Glaetzer, You could see why Wolf Blass was a juggernaut with these guys directing the winemaking.’

David O’Leary still relished the chance to make some great whites, and Annie’s Lane was a place where many great Rieslings had come from. ‘I would always check with Nick Walker on making Riesling,’ David stressed, ‘as he was part of the group and ran the Krondorf winery pretty much since we graduated from Roseworthy.

Nick said David should talk to Chris Hatcher, so he did. ‘During vintage I would annoy Chris and Wendy Stuckey on how they went about making Riesling,’ David recalled, and one of his Annie Lane Rieslings soon won a gold medal at the Adelaide show – he was making Rieslings under 4 different labels at Annie’s Lane.

Chris Hatcher accepting yet another Best Winemakerr Award.

David’s new talent with Riesling didn‘t go unnoticed. ‘As I passed Chris Hatcher at work one day,’ David recalls, ‘he said “did you soak the label off a Wolf Blass Riesling?” ‘I was lucky to work with Chris,’ he concedes. Hatcher has won over 200 gold medals and trophies.

Good Bye Barbarians

In 1998, David was dispatched to Coonawarra to run Mildara’s operation there after Gavin Hogg resigned. A year later David O’Leary resigned and joined forces with Nick Walker in their new venture – O’Leary Walker Wines. ‘Everyone told us we were mad,’ David recalled, ‘to give up our well-paid jobs and go out on our own.’

One thing the two weren’t short of was experience: Together, they had worked in the wine industry for over half a century. Nick’s father Norm Walker once made sparkling wine for Romalo and Seaview. His father Hurtle worked with Frenchman Leon Mazure, making sparkling wine at Auldana and Romalo. In memory of his dad, Nick Walker has been making a ‘Hurtle’ Sparkling Pinot Noir Chardonnay.

Nick spent over 14 years with Mildara Blass making wine for Yellowglen, Yarra Ridge, Baileys and St Huberts labels. He had cut his winemaking teeth at Krondorf in the early 1980s, where he made Eden Valley Rieslings that won a ton of bling on the show circuit.

3 generations of the Walker family

Grant Burge bought the Krondorf winery in 1978, sold it to Mildara Blass in the eighties, bought it back in the nineties and sold it to Accolade in 1999. He bought the winery for a third time in 2022, from Accolade Wines after they closed it down – a perfect example of the madness that is the wine business down under.

‘We had planned to set up shop in the Adelaide Hills,’ David told me, ‘but the council only approved a dozen licences and we missed out.’ David grew up in the Hills, and his family owns several vineyards there, but he and Nick ended up in the Clare Valley where they leased the mothballed Quelltaler winery for $50,000 a year.

That was a blessing in the first few years, but then the owners kept raising the rent, so David and Nick decided to build their own winery which was completed in 2010. They didn’t plant a vineyard in Clare since they knew the best growers in the valley to buy fruit from. They made wines from the traditional varieties – Riesling, Shiraz and Cabernet. The model was to make small batch, high quality wines from the best sites in South Australia.

The Hills are Alive

In the nineties, David planted lots of vines at Oakbank in the Adelaide Hills, some on the original ‘Wyebo’ property that his grandfather bought in 1912. The varieties they planted here were Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay, Merlot, Malbec and Shiraz..

That meant David and Nick had 2 styles of wines for sale: the traditional Clare styles, and the more modern, cool climate Adelaide Hills styles.

In 2015 they bought the old Johnston family brewery and cordial factory beside the Oakbank racecourse, and turned it into a cellar door and restaurant.

‘These days you need to offer tourists a lot more than just wine,’ David explains. ‘They want a more complete experience, and you want them to come back for more.’ That’s why their winery in the Clare Valley employs a full-time chef today.

Business was flourishing until Covid reared its ugly head. We all know about the damage the pandemic did to restaurants and coffee shops, but we didn’t hear about the damage the virus did to wineries that relied on supplying restaurants or on their cellar door trade. Covid even impacted on their exports.

‘Covid was very tough and I feel for a lot of businesses especially in Victoria,’ David recalls. ‘Our Sales were mainly to on premise restaurants and independent retail, which was closed down. Our sales domestically were down 75%, which was really tough.’

Early in 2021, they had to close their cellar door at Oakbank in the Hills, and sell the historic brewery site. ‘The only good thing Covid did,’ David summed up, ‘was make us really have a critical look at our business and how we can improve the running across the board.’

Export wasn’t a high priority until now, and O’Leary Walker was among 10 South Australian wineries selected in the Wine Australia USA Market Entry Program in 2020. Nick Walker’s son Jack has been learning the ropes in the winery for several years now, so perhaps the need for David to work nightshifts will reduce.

Footnote

This was a big story, covering the working lives of two winemakers, and I needed a lot of help with the details. David O’Leary was always happy to answer question by email or phone, was always helpful and showed endless patience.

As I said earlier, he was more than generous in his praise for the many people he worked with. That includes Wolf Blass, the great self promoter – David expressed nothing but admiration for Blass’s achievements. When you search for Wolf’s interview with Richard Fidler on ABC radio in 2011, this is what the entry in the search results says: ‘Wolf Blass has played a major role in transforming Australia into one of the world’s most respected winemaking countries.’

According to Wolf, Australia was the vinous equivalent of Terra Nullius. Everyone drank beer, he said. The red wines we made were awful. He told Richard about his many achievements, about how smart a winemaker he was, and about his marketing genius.

He rarely talked about anyone else. Forget Max Schubert, Maurice O’Shea, Jack Mann, Ron Haselgrove, Roger Warren, Colin Preece or John Vickery. When you listen to Wolf in his radio interviews, these guys simply didn’t exist.

Yes, the German Genius came to this backward land and civilised it all by himself. More here: Wolf Blass Wunderkind?