It’s OK: the judges can’t tell a $20 from a $100 wine either

This is a rolling post we update from time to time with the latest news

The poor correlation between wine prices and wine quality is the story of our website, the bedrock we built it on, our raison d’être. The evidence keeps building that the story won’t change anytime soon. 2014 hasn’t provided as much support for our premise as did 2013, but here’s whay we have so far:

$25 SC Pannell Shiraz takes out 2014 Jimmy Watson Trophy. Made famous by Wolf Blass, this trophy has been given for more weight in recent years, so it’s not surprising that the wine flew off retailers shelves. Pulpit Cellars in the Adelaide Hills is one of the few places where you can still buy it. The even better news is that the $13 Lock & Key Siraz 2013 from Moppity Vineyards in the NSW Hilltops was the runner up on 97 points.

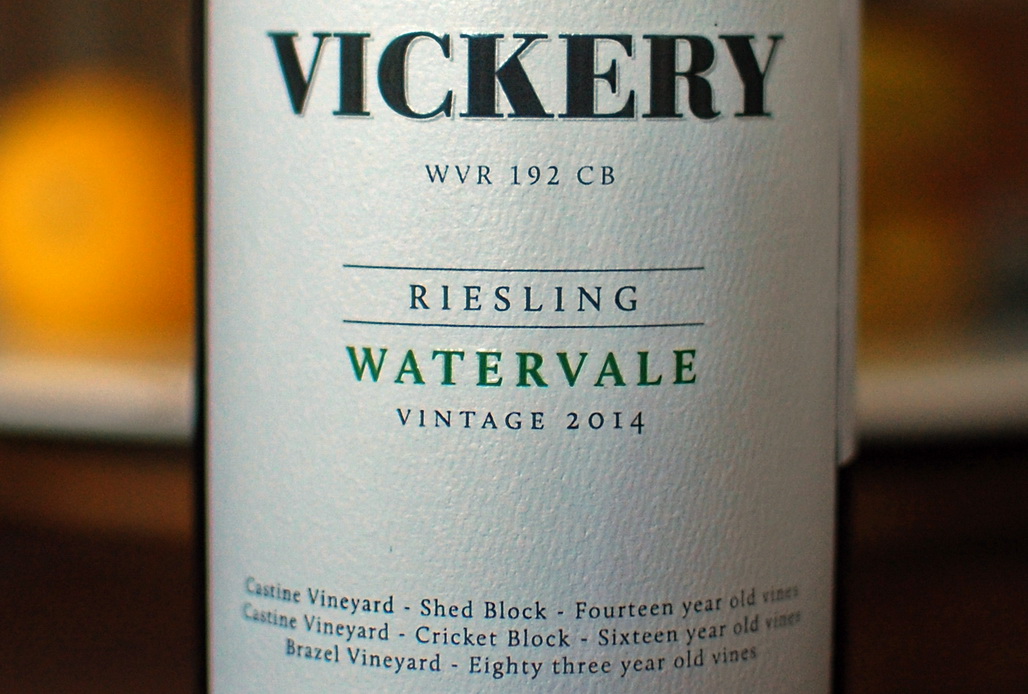

$20 Mudhouse Riesling 2013 wins Canberra International Riesling Challenge. This was a double act of validation for our premise, in fact, since the $18 Heggies Botrytis Riesling 2012 took out the trophies for best Australian Riesling and best sweet wine of the competition (Sixty Darling Street 02 9818 3077, sales@wineroom.com.au).

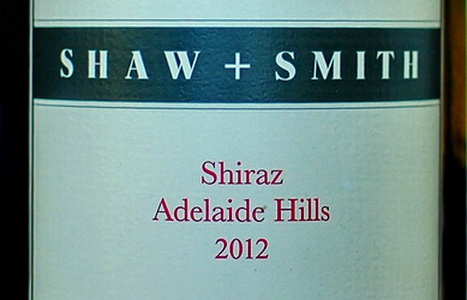

The Best Red in Australia is a $35 Shaw & Smith Shiraz. So said the judges at London’s International Wine Challenge back in June. The Shaw and Smith Shiraz 2012 is $37 at Winestar. It’s not quite in our price range, but it proves our premise that you don’t have to spend a fortune to get your hands on a great wine.

St Henri 2010 steals the show. Another wine not quite in our price range, except that it sold briefly for $62 a bottle. Anyhow, the least sexy wine in the Penfolds line-up of icons bowled over all its more expensive siblings and came out on top with a 100 point score in 2014. In the major stores, it sold out in a day.

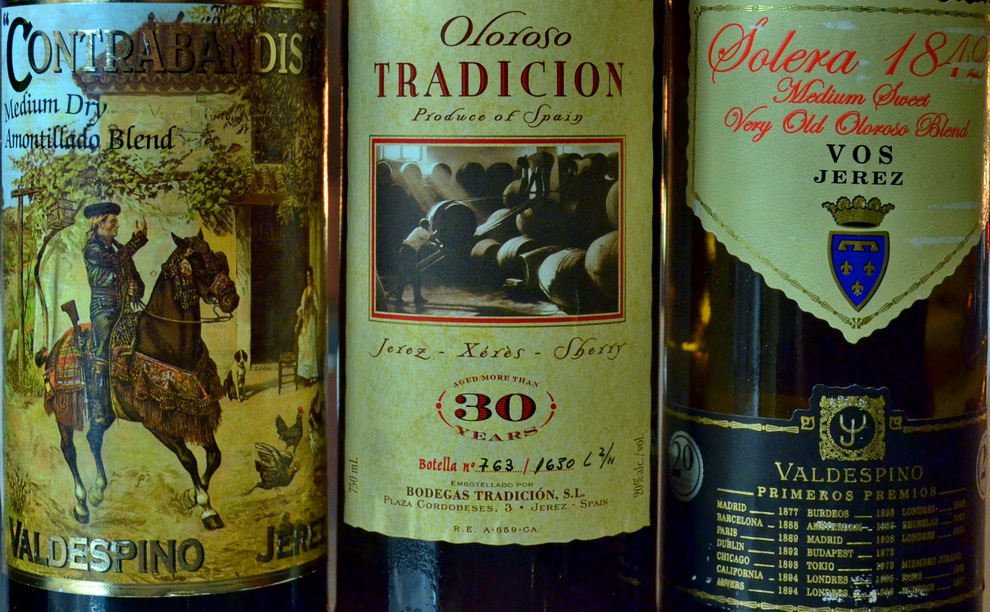

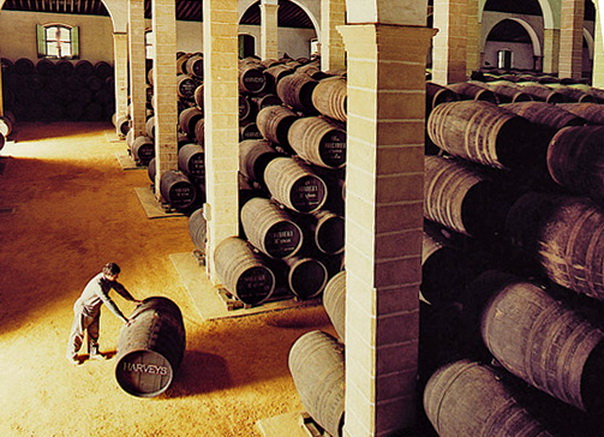

From left to right: Fino, Amontillado and Oloroso

From left to right: Fino, Amontillado and Oloroso