The wines we drink have changed a lot in the last few decades, whether they’re Australian or imported. Reds have changed most of all: they’re bigger, richer and softer, they’re more fruity and less tannic these days. Most commercial reds are ready to drink when they’re released 2 or 3 years old, therefore the question in the title of this post.

What about the big guns?

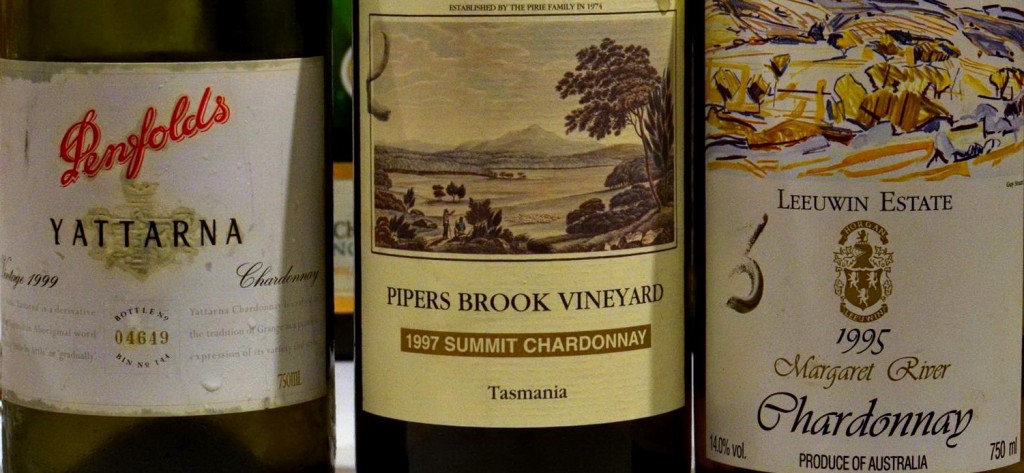

Grange and its iconic siblings are still made for the long haul, and will repay some years in the cellar. So will the top of the line Henschkes, Torbrecks and Brokenwoods, the serious reds from Leeuwin Estate, Cape Mentelle and Wendouree. Some of our best Rieslings and Semillons will improve for a decade or more as well.

What about the great names of Bordeaux and Burgundy, Italy and Germany? The Wine Spectator’s Matt Kramer raised the cellaring question not long ago and concluded that ‘most of today’s fine wines will reach a point of diminishing returns on aging after as few as five years of additional cellaring after release.’ He added that even great Bordeaux and Burgundies, and the best Brunello di Montalcino or Barolo wines would repay 10 years of cellaring at most.

Green Harvests

The main reason Kramer gives is ‘green harvests’, the practice of taking green bunches of grapes off the vines a few weeks before harvest. This practice, which wasn’t widespread until the 1990s, results in uniformly riper grapes. Kramer says the practice ‘has transformed the quality of fine red wines nearly everywhere, ensuring more uniformly ripe grapes with rounder, softer, finer tannins.’

Kramer adds that cleaner winemaking, malolactic fermentation and the practice of maturing reds in small oak barrels have also played a role in making today’s wines are far more drinkable than their counterparts of 20 years ago.

Later Harvests

Kramer only mentions the recent trend of ultra-ripe late picking in passing, which is a little strange given that it has the most obvious effect on bringing wines forward. The riper and richer red wines are, the more appealing they are in their youth. As they age, they tend to fade rapidly like so many Mediterranean beauties but it’s easy to forget that when confronted with the blush of youth.

Most wine judges and reviewers fall for the lush young beauties, and winemakers haven’t been slow to notice. ‘There is a race towards concentration, to please many critics [read Robert Parker],’ Professor Denis Dubourdieu told Decanter magazine. He said later picking – sometimes even after the Sauternes harvest in October – had become common practice.

Most wine judges and reviewers fall for the lush young beauties, and winemakers haven’t been slow to notice. ‘There is a race towards concentration, to please many critics [read Robert Parker],’ Professor Denis Dubourdieu told Decanter magazine. He said later picking – sometimes even after the Sauternes harvest in October – had become common practice.

Jean Claude Berrouet, formerly at Petrus and now winemaking director for various estates in Pomerol, told Decanter that he had seen alcohol levels rise between 2 and 2.5 degrees in his 40-years of winemaking. The 2009 and 2010 Bordeaux reds support his claims, with alcohol readings of 14.5 to 15% – details HERE.

The Gamble of Long Term Cellaring

I’m lucky to be part of a group of wine lovers who have deep cellars, and we get together every few months for dinner. We all bring a bottle or two of our finest, and at least half of them are either over the hill, or disappointing, or dud bottles. Yes, you end up with quite a few duds over the years.

In the cold, hard light of day, this is what happened: you bought a $100 bottle of wine and stored it in your purpose-built cellar for 25 years. It’s now worth $2000 but it’s a dud. You can’t even get your $100 investment back, let alone present value. If you’d bought bought 5 shares in Microsoft at its IPO in 1986 for $105 instead, they would’ve turned into 1440 shares over the course of nine stock splits and would be worth about $37,000 today.

Age is overrated

The longer you keep a wine, the higher the chances that you’ll be disappointed. That’s because age throws a harsh light on character flaws, as it does with people. At every one of these dinners, I come away thinking that the good wines we shared would’ve been better 10 years ago (excepting the fortified wines).

One night in 2012, we shared four 1982 Grand Cru Bordeaux including first the growths Latour and Haut-Brion. Even these fabled wines from a fabled vintage would’ve been better ten years earlier. There are sublime exceptions: a 1976 Grange was at its absolute peak in the same year, and so was a 1975 Chateau d’Yquem.

One night in 2012, we shared four 1982 Grand Cru Bordeaux including first the growths Latour and Haut-Brion. Even these fabled wines from a fabled vintage would’ve been better ten years earlier. There are sublime exceptions: a 1976 Grange was at its absolute peak in the same year, and so was a 1975 Chateau d’Yquem.

The thing to remember is this: if you open a bottle and think the wine is good but needs a few more years to reach its full potential, you’ll most likely enjoy it anyway. If you open a bottle and think it would’ve been better 5 years ago, the disappointment will linger. If you have more bottles of the wine in your cellar, the disappointment will linger longer.

Back to the Real World

I’ve just updated our list of Best Cellaring Wines under $20, and it’s a real struggle to find wines – red or white – that will improve for more than 3 -5 years. As you can see from the examples below, among the safest cellaring bets are Aussie Rieslings and Semillons made the traditional way.

| Pepperjack Shiraz 2012/3 | 3 – 8 years |

| Knappstein Cabernet Sauvignon 2012 | 3 – 10 years |

| Mildara Coonawarra Cabernet Sauvignon 2012 | 3 – 7 years |

| Lake Breeze Cabernet Sauvignon 2012 | 3 – 10 years |

| Lake Breeze Shiraz Cabernet 2012 | 2 – 8 years |

| Balnaves the Blend 2012 | 3 – 7 years |

| Frogmore Creek Riesling 2013 | 7 – 10 years |

| Mount Majura Vineyard Riesling 2014 | 7 – 12 years |

| Mandala Yarra Valley Chardonnay 2013 | 3 – 7 years |

| Tarrawarra Estate Chardonnay 2012 | 3 – 5 years |

| Tahbilk Marsanne 2014 | Now – 15 years |

| Thomas Wines Braemore Semillon 2014 | 7 – 15 years |

| De Bortoli Deen Vat 5 Botrytis Semillon 375 | Now to 7 years |

How can we tell if a wine will improve for 5 – 10 years? Two ways: We look for a good structure, that is: depth of flavour, line and length of fine acid (in white wines) and a decent tannin grip on the finish of red wines. The fruit may be subdued and the component parts may be immature and edgy, but the wine must show good balance overall. It’s not easy to explain in words, but experienced tasters think they can tell (yours truly included).

As with the weather, the further ahead you forecast the more uncertain things get. That means the longer you keep a wine, the greater the gamble. This is why reviewers of thoroughbreds look at the bloodlines. If a wine has a history of aging well over 20 years, it’s a safe bet that the new wine of a good vintage will follow suit. That’s if all else is equal, the winery hasn’t changed hands, and the winemaking team is still the same.

Corks and Stelvin caps

The screwcaps have banished cork taint but have had no impact on winemaking for obvious reasons. Most of us expect them to slow down the aging process but that’s not yet been proven beyond doubt. If it’s true, it may help keep some wines alive a bit longer which could be a good thing given the shorter lifespans of most modern wines.

The screwcaps have also had an impact on ‘laying wines down’, since they can now happily stand up in your cellar. Of course, most of us down’t have a cellar in the traditional sense so we’ve put together our Rough Guide to Cellaring Wine in a Hot Climate to show you some practical options.

The screwcaps have also had an impact on ‘laying wines down’, since they can now happily stand up in your cellar. Of course, most of us down’t have a cellar in the traditional sense so we’ve put together our Rough Guide to Cellaring Wine in a Hot Climate to show you some practical options.

Kim