Exciting time or waste of time?

These are the days of miracle and wonder … (Paul Simon)

Exciting new grape varieties have been making waves across our lakes of surplus wine, led by the Italians: Sangiovese, Nebbiolo, Barbera, Fiano, Arneis and Vermentino. Then we’re seeing more Tempranillo from Spain, Lagrein & Gruner Veltliner from Austria, Tannat from South Western France and Saparavi from Georgia.

The question I can hear some of you are asking is this: are these just new fad varieties for sommeliers to amuse themselves with and confound their clientele, or do they actually have some merit? Before we answer that question, a little history will help shed some perspective on this subject.

The question I can hear some of you are asking is this: are these just new fad varieties for sommeliers to amuse themselves with and confound their clientele, or do they actually have some merit? Before we answer that question, a little history will help shed some perspective on this subject.

The Riesling era

Some of you will remember the Chardonnay boom of the eighties, and the excitement that went with it. Here was a new kind of white that was different from the Rieslings we drank back then. Yes, Riesling was king back then, so much so that we had 3 kinds of it: Semillon from the Hunter, Riesling from South Australia, and an obscure variety called Crouchen. They were called Hunter River Riesling, Rhine Riesling and Clare Riesling, and they were the white wines most people drank then.

Sure there were other white varieties: there was a bit of Chenin Blanc over in the Swan Valley which Jack Mann used in Houghton’s White Burgundy. There were a few acres of Trebbiano planted here and there. The variety is the backbone of Cognac but Cyril Henschke once made a Trebbiano he labelled Ugni Blanc (one of its many synonyms). Henschke also created a dry white Frontignac, an aromatic white wine made from Muscat of Alexandria. The style lives on today in Stanley’s fruity Lexia sold in 4 litre casks.

Henschke was a pioneer of varietal labelling in the early sixties, when most of our wines were labelled Hock, Moselle, Chablis, White Burgundy, Burgundy and Claret. By the seventies, these descriptors had been banished to the bulk wine end of the market. By the eighties, they were banished altogether once the French began talking countries to court for pinching their names.

Fruit salad days

Once varieties became common on labels, punters looked for uncommon varieties. Verdelho reared its head on an obscure label here and there. Traminer saw a short burst of popularity and had to be blended with Riesling to meet the sudden demand. Traminer Riesling is another fruity white that has survived in 4 litre casks. The best Traminer in those days came from Penfolds Minchinbury vineyards in western Sydney. It was labelled Trameah.

There were a few rows of Aucerot and Blanquette (Folle Blanche) in the Hunter (the fruit was usually blended with Semillon), and some Irvine’s White in Great Western which went into the bubblies they made there. A few Marsanne vines survived at Tahbilk, and so did Chasselas and Colombard vines in South Australia.

Penfolds used to make a Pinot Riesling from their Hunter Valley Distillery vineyard, which was a blend of Pinot Chardonnay and Semillon. The Pinot was thought to be Pinot Blanc or White Pinot until the CSIRO invited a French ampelographer (an expert on grape varieties), Dr Boubals from the University of Montpellier, to help us sort out what was what.

Pinot Blanc and Pinot Chardonnay are notorious for confusing vignerons, so similar are the vines and leaves and fruit in the vineyard. There’s more on that in the story Where did Murray really get his Chardonnay from?

Vineyards at Condrieu in the Northern Rhone Valley, where the world’s best Viognier is made

Vineyards at Condrieu in the Northern Rhone Valley, where the world’s best Viognier is made

The ABC of Wine

An excess of Chardonnay in the eighties and nineties caused the Anything But Chardonnay backlash by the new millennium. Wine has long been a fashion business, and punters had discovered Sauvignon Blanc. Viognier and Pinot Gris also built small followings. Yalumba’s untiring efforts to establish Viognier as a major variety in this country have paid off, but it took a lot of work and a lot of money and a couple of decades. The next quote illustrates some of the difficulties.

‘AUSTRALIANS are famously inept at pronouncing foreign names,’ writes Charles Gent, ‘and wine nomenclature is no exception. A few years ago, when Yalumba made a big push to promote a new white wine variety with origins in the Rhône valley, large banner advertisements resorted to spelling out the French name in phonetics: VEE-ON-YEE-AY.’

The Southern Rhone trio of Marsanne, Viognier and Roussanne is gradually joining the establishment, only held back by limited supplies. They were thought to do best in our warmer vineyard areas, but the best of these wines are coming from cooler places. That’s not surprising given that the Barossa is probably a fair bit hotter than the Provence.

The Alsace Trio of Riesling, Pinot Gris and Traminer is two thirds of the way there, with Traminer dragging the chain. Again, the best of these come from our cooler regions. The rest of the fancy new white varieties – Fiano, Arneis, Vermentino & Gruner Veltliner have yet to make an impact, at least on our palates. We’re not convinced that any of them have a serious future here.

Grenache the Sleeper

In the sixties, there were Shiraz vines as far as the eye could see – from the Hunter to the Swan Valley. There was very little Cabernet Sauvignon, and it was well into the seventies before new plantings put an end to the shortage. The need to stretch the rare Cabernet with the ubiquitous Shiraz led to a blend that has become Australia’s own.

Grenache was in fact a close second to Shiraz in South Australia in quantity produced, but most of it didn’t go into red table wines – it went into port wine and brandy. That’s because Grenache in South Australia’s hot summers would easily ripen to a hefty 15 – 16 degrees Baumé, which translates to roughly the same percentage of alcohol in a dry red.

Some of our Grenache went into Rosé. Orlando’s Grec Rosé was made from Grenache, and so was Hardy’s Mill Rosé. Occasional BWU$20 contributor Richard Warland conceded recently that the 1973 Mill Rosé he made for Hardy’s, which won the Championship Trophy at the Adelaide Show that year, had an ‘illegal’ (for table wine) alcohol level of 15.6%. As flagons and casks became popular, Grenache found another home because of its sweet fruit and easy drinking qualities.

Discovering the Rhone blend

Our shabby treatment of Grenache is hard to understand given the key role the variety plays in the table wines of the southern Rhone, and as Garnacha in Spain. One producer bucked the trend: D’Arry Osborne at d’Arenberg in McLaren Vale with his Burgundy (now labelled Shiraz Grenache). It was ‘a crowd-pleasing favourite,’ recalls Richard Warland, ‘exhibiting all of the glorious flavours and spice of open-fermenter, basket pressed McLaren Vale Grenache …’

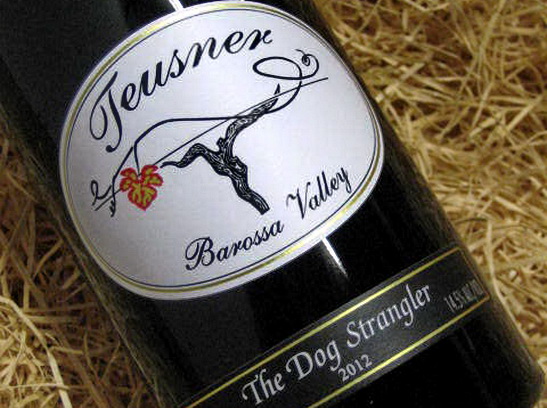

By now, the Rhone Trio of Grenache, Shiraz and Mourvèdre is so well established that most of us are familiar with the GSM acronym. Mataro was another variety we treated badly down under until we learned that it was in fact Mourvèdre, and until Robert Parker raved about a few big reds made from old Grenache, Shiraz and Mourvèdre grapes. This is one variety that needs to be given time to fully ripen, which it does later than most varieties, and that avoids the ‘dog strangler’ tannin grip the variety is known for in Europe.

In the state government sponsored vine-pull scheme of the mid-eighties, a lot of old Grenache, Shiraz and Mourvèdre vines were grubbed out by South Australian vignerons who were stuck with red wine they couldn’t sell (the fashion had swung to white wine – more in Why the French Hate us). We’re pretty lucky that some vignerons gritted their teeth and hung onto their old vines.

Bordeaux and Burgundy

Given all the reds that were sold under Claret and Burgundy labels in the sixties, you may be surprised to learn that we didn’t even have the grape varieties these styles are made from in their home countries. We had little Cabernet and no Merlot, which is an essential part of the Bordeaux style. We had a little Malbec which was falling from favour over there, but no Cabernet Franc or Petit Verdot.

In the eighties and nineties, we planted a lot of Merlot and some Cabernet Franc, and even some Petit Verdot. Margaret River has pretty much made Cabernet Merlot blends its signature red. Just why Malbec hasn’t been more successful is a good question. The old Clare Valley Cabernet Malbec blends of Stanley (Bin 56), Wendouree and Tim Adams show just how well these combos work.

Red Burgundies are made from Pinot Noir and that variety has long been a primadonna even in Burgundy. It’s taken Aussie winemakers several decades to work out the most suitable clones for their vineyards and the best wine making processes. The result is that we’re making some good Pinot Noirs in some places in some years. The Kiwis seem to have done a little better.

The only other variety of consequence is Durif, and most of it is grown around Rutherglen. Durif tends to make very robust wines of enormous alcohol content, and is probably better suited to port making.

New kids on the block

Sangiovese, Nebbiolo, Barbera and Tempranillo are being made by a surprising number of wineries now, and some decent wines have resulted. None that have shown the same kind of promise as the originals in Europe, mind you, so we need to reserve our judgement here. Lagrein, Tannat and Saparavi, on the other hand, have yet to show that they have more to offer than the appeal of mysterious novelty.

Kim