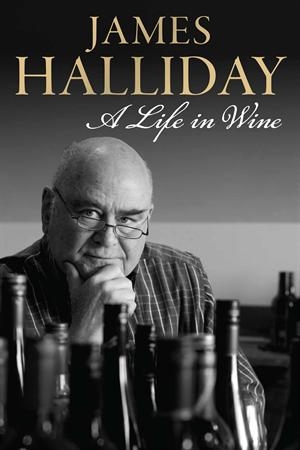

Not a book review, more a note to the author

Dear James,

Over many decades, you’ve written many books on wine that gave us insights and knowledge. We stand in awe of your achievements and your capacity for work, which is that of 3 ordinary men. How many of us can claim two lighthouse winemaking ventures, and authorship of over 50 books? All while holding down a high-powered job? Not to mention more wine tastings and dinners in numbers that would’ve killed ordinary men long before their prime.

You always assigned yourself a backseat in your writings, giving centre stage to wine, so I couldn’t wait to read this story of your life. A good friend warned me that it was disappointing, but I chose not to believe him. Sadly, he was right: This was the most important book of your life, and it should’ve been much more exciting than it is.

Where is the colour?

I wrote of Len Evans recent ‘Not my Memoirs’ that it was like a colouring-in book, in the sense that the characters were only drawn in outlines. The same comments apply to your story, only more so. Len Evans is the exception in your story: you do make a decent attempt to capture the spirit of the great man, an impossible challenge by all accounts.

The rest of the wine men you shared so much more than rare bottles with pass by as shadows mostly, not as the great characters they are. You were right there in the front row with them, from Bulletin Place to Brokenwood to Bordeaux and Beyond: John Beeston, Tony Albert, Rudy Komon, Murrray Tyrrell, Hermann Schneider, Brian Croser and more.

The many photos in the book often tell more of the story than the words, but form a somewhat disconnected record of the characters and events.

Where are the people?

Surely, this story should’ve been more about people than wine, James. Lots of them are mentioned, but we get close to none, really, and we get no sense of the passion for wine and wine collecting and wine making that consumed their lives. Why not? How did their wives feel about them investing the family’s savings in rare bottles and fancy dinners and high-stakes winemaking ventures?

We get some details on how Brokenwood came about, and how it was built and grew. We get some details on who else was there and who helped. Same with Coldstream Hills, with more emphasis on the finances and the neighbours. We don’t get a lot of anecdotes, when there must’ve been thousands, and the ones we get aren’t that funny – I didn’t laugh more than once or twice during the entire story.

There aren’t enough tears either, or sweat or pain or even wine stains. Your story never really comes alive and touches us. It feels more like you had to write it than like you really wanted to.

Where are you, James?

We don’t even get to know you, James. Sure, we get to know James Halliday the wineman, James the gourmand, James the winemaker and the lawyer and so on. We don’t really get to know James Halliday the man, the husband, the father, the friend.

We get no sense of how much of a gamble the Coldstream Hills venture was, and how much more of the risk you had to shoulder on your own. We get a sense of the financial burden, yes, but no sense of the agony and doubts and pain you must’ve felt at times.

Reading your story feels a lot like sitting in the kitchen while you and your friends are having a ball in the dining room, talking and laughing and eating and drinking. We get a sense of what people are saying, but can’t quite make out the words. We see the empties the next day and admire the labels.

What is the point?

One place where we’re allowed to get closer is the food and the wines consumed by you and friends at the best restaurants in France, England and back home. Here we get all the details of every course and every bottle opened, time and again, but what is the point? Most of us never have, and never will, drink 60-year old Bordeaux grand crus or Burgundies from the Domaine de la Romanee Conti, and very few of us have drunk wines from the previous century.

Even an all-Australian Single Bottle Club Dinner offered nothing we ordinary mortals could relate to, since the bottles selected included Seppelt Great Western wines made by Colin Preece between ‘49 and ’54, ’53 Grange and ‘37 Mount Pleasant Mountain A. The youngest wine was a Lindemans Porphyry ’56. Do we really need a whole chapter on these dinners, in addition to the many occasions you describe?

If we have little chance of ever tasting these wines, James, how about telling us what they tasted like? As it stands, your detailed listings of these wine dinners are exercises in extraordinary futility. As an experienced writer, you should know that readers will switch off if they have nothing to relate to, unless your description of the people and the events is so colourful that they can sit back and enjoy the spectacle.

Where was your editor?

A real surprise was the clunky writing in this book. I’ve read most of your books and your writing has always been competent, lively and engaging. The writing in this one is often clunky, not what I’d expect from someone who has your known facility with words. Did your publisher provide an editor on previous occasions but not on this one? Or did you think you no longer need one?

Sad to say, my friend was right. This is a boring book, James, and I only finished it because I wanted to write a review for my website. I’m not sure who your target audience is, but if guys like me aren’t captured by your story, there’s something wrong. I say that because my friends and I have been mad about wine for almost as long as you, and we’ve spent fortunes on fancy wines and dinners as you can see.

James, I really wish I could’ve been kinder. For many years, I’ve stood in awe of what you’ve accomplished in one lifetime, and I remain an admiring fan of your work if not of this book.

James, I really wish I could’ve been kinder. For many years, I’ve stood in awe of what you’ve accomplished in one lifetime, and I remain an admiring fan of your work if not of this book.

Kim