How two white knights saved a mismanaged company

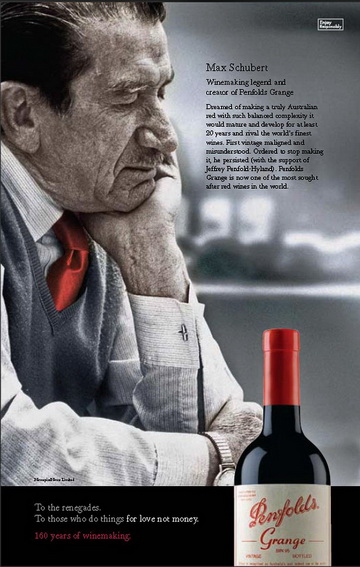

‘Max Schubert and Grange helped transform Penfolds from being makers of cheap fortifieds into one of the great wine companies of the world.’ Richard Farmer.

Max Schubert will forever be known as the Creator of Grange, the Genius who created Grange or the Father of Grange. Everyone knows the story of Max being ordered to stop making Grange because the early reviews were scathing, and the timid people who ran Penfolds couldn’t see past their noses.

Few will remember that, as winemaker, Max Schubert improved every wine Penfolds made, or that he improved every wine-making process when he was Penfolds’ Production Manager, or that he optimised the output from every vineyard and winery Penfolds owned.

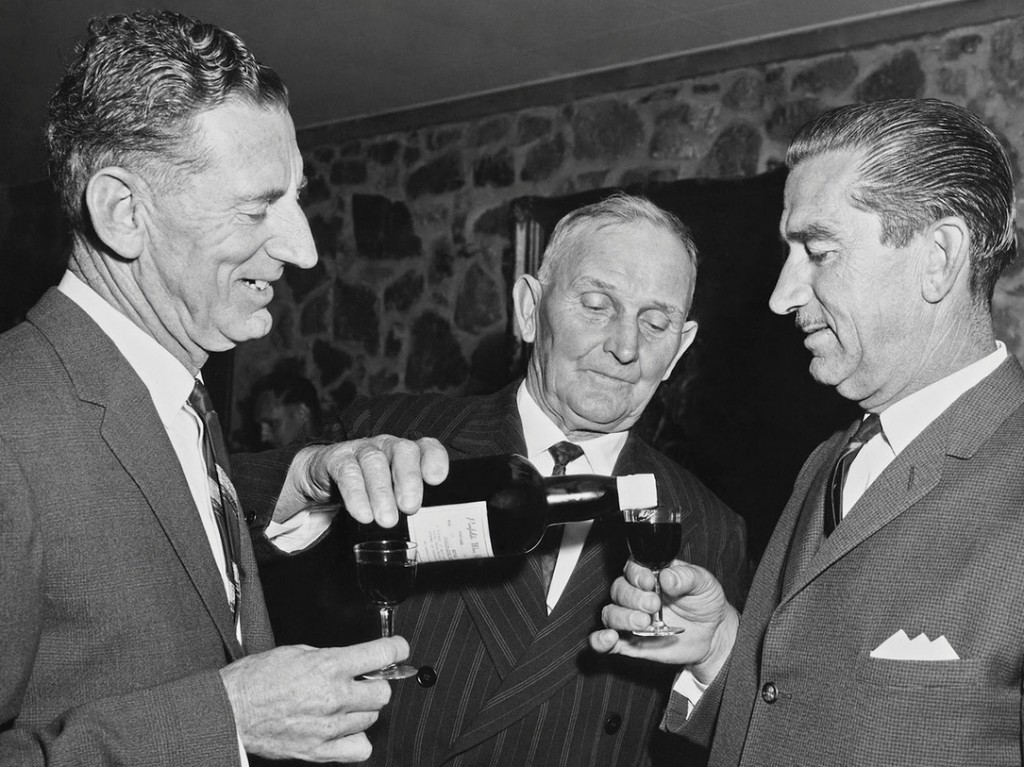

Ray Beckwith, Alfred Scholz and Max Schubert enjoying a spot of Grandfather Port – photo credit: Milton Worldley

Ray Beckwith, Alfred Scholz and Max Schubert enjoying a spot of Grandfather Port – photo credit: Milton Worldley

Max had a lot of help from Ray Beckwith and others in turning Penfolds from a maker of cheap ports and brandies into a powerhouse table wine company, but he was the driving force. It’s not well-known that Max was a heavy smoker most of his life, and that he died of emphysema in 1994.

For Love or Money

Treasury Wine Estates owns the Penfolds brand today. TWE is the company Fosters hived off in 2012 before selling its beer business to South Africans. TWE has a lot of urgent work to do restoring the great brands Southcorp and Fosters trashed in the naughties, brands like Lindemans, Leo Buring, Mildara, Rosemount, Rouge Homme, Saltram, Seppelt, Seaview and Wynns. Sadly, TWE has decided that milking the Penfolds brand for more than it’s worth is the easiest way to keep the money pouring into its coffers.

As Richard Farmer reminds us, only a couple of years before Fosters decided that wine was a distraction to its beer business, it ‘realised that selling wine was not the same as selling beer … So what to do now? Why, let’s go back to pretending that we are once again artisan winemakers. Resurrect that old bloke who invented Grange. Putting him on the billboards won’t cost us anything because he’s long dead.’ More HERE.

The campaign ran under the banner To The Renegades, which proved that Fosters wasn’t just ignorant about wine but about the English language as well. Max Schubert was a company man through and though. He might’ve been a bit of a maverick but he was no renegade. And here’s an ironic twist: the tagline for the ads was ‘To those who do things for Love not Money.’

Shabby as shabby gets

Max worked for Penfolds all his life yet Penfolds didn’t seem to appreciate his enormous contribution, as Richard Farmer reminds us: ‘The loyal servant of Penfolds had always hoped his farewell would be celebrated in that old fashioned way with a good watch. A Swiss Rolex was to be his pride and joy but he just got a Japanese Citizen, and for the rest of his life there was not even a free case of his masterpiece every vintage.’

This is staggering to read given that Max retired in 1975 (see below), just before the Penfold family sold out to Sydney brewer Tooth & Co. Max had to look elsewhere for recognition, which came years later in the form of the inaugural Maurice O’Shea Award, an Order of Australia, Decanter magazine’s Man of the Year in 1988, and an Australia Day Citizen Award in 1991.

Chris Shanahan said in his 1994 obituary: ‘Like Patrick White and Sydney Nolan, Max Schubert’s genius blossomed in the early 1950s despite a post-world-war-two Australian culture that could hardly have been more hostile to originality and unconventional ways.’

A time for Change

Max Schubert’s life has been examined in great detail by many others, so we’ll confine ourselves to teasing out some lesser-known insights. Penfolds is always described as a great wine company, but it was a company beset by enormous problems when Max began working for it. As Huon Hooke chronicles in his book (Max Schubert, Winemaker, Kerr), much of the fortified wine Penfolds produced between the wars was contaminated.

‘Mousy’ wines were a huge problem at the time. Max said they used to clean the worst of them up with charcoal, and then add caramel to put back some of the colour lost in the process. The wines had to be bottled and sold quickly before ‘the mouse’ reared its head again. Metal contamination was another serious issue that Max eventually solved by replacing metal containers and hoses with PVC.

Bacterial spoilage was a huge problem until Ray Beckwith applied some serious science to Penfolds’ winemaking. Ian Hickinbotham, a brilliant oenologist and innovator said: ‘Let’s be blunt – there would have been no Grange without Beckwith’s brilliance. Possibly, Beckwith contributed more to Australian oenology than any other and he should be recognised in the same class as Louis Pasteur.

Breakthrough science on pH

‘Dr Ray Beckwith is one of the unsung pioneers of the modern Australian wine industry,’ Andrew Caillard writes in Penfolds – The Rewards of Patience. ‘His interest in the performance and efficiency of winemaking yeasts lead to an important association with Alan Hickinbotham (Ian’s father) – a pivotal figure in Australian wine science and whose work in pH and malo-lactic fermentation would have profound generational effect on winemaking philosophy.’

Ray Beckwith joined Penfolds at Nuriootpa in 1935. One of the first things he noted was that ‘the heat of fermentation was a major problem because too much heat resulted in the loss of quality and the prospect of bacterial spoilage.’ Crude copper heat exchangers were used to cool things down in those days, and sometimes ice blocks were thrown into the fermenting vats.

Beckwith built a new laboratory and a yeast propagation tank, and then persuaded Leslie Penfold Hyland to buy him an expensive pH meter with the Morton glass electrode. The rest, as they say, is history: the importance of pH in stabilising wine, the contribution to table wine quality made by the secondary malolactic fermentation (that converts malic acid to the softer lactic acid), and the simple trick of lowering pH after the ‘malo’ with the addition of tartaric acid, a natural constituent of wine.

Ian Hickinbotham gives us a commercial context for Ray’s achievements: ‘Beckwith applied his unique knowledge to the making and husbandry of all wine types – with remarkable cost savings – when employed by Penfolds for the rest of his working life. In a nutshell, he saved the 25% wine component that previously had to be destroyed by distillation due to bacterial spoilage. From that time, around 1940, Australia became a world leader in the making of table wine.’

Ray Beckwith won the prestigious Maurice O’Shea Award in 2005, was awarded an Honorary Doctorate from the University of Adelaide, and in 2008 – at the age of 96 – the Order of Australia ‘for service to the Australian wine industry through contributions towards enhancing the quality and efficiency of the winemaking process.’

It’s just as well Ray lived to 100. For most of his life, he was the unsung hero in the Penfolds saga. In an interview a few years ago, he said: ‘All these things have come only after the last few years. It’s a good thing I didn’t conk out earlier, otherwise I wouldn’t have known!’

‘Petticoat Government’

Huon Hooke tells us that Dr Christopher Rawson Penfold gets all the credit for building the famous brand, but that his wife Mary actually ran the business while the doctor practiced medicine. She continued to do so for a quarter century after his early death. A century later, Frank Penfold-Hyland is described as a misogynist who sees no place in the business for his daughter Rada and sends her to London where she lives the high life (but was of more help to Max than he expected).

When Frank died in 1948, his wife Gladys inherited his majority shareholding and became chair of the company. Frank had groomed General Manager Des Hawke to take over as Managing Director but their relationship deteriorated, so Frank gave the job to his loyal secretary Grace Edna Longhurst. So now we had two women who knew nothing about wine running Penfolds, and the press was quick to dub the duo ‘the Petticoat Government.’

Gladys is described as a domineering woman in this source ‘… stocky in build, she generally dressed in beautifully tailored suits, often with initialled brass buttons … She lived in an old Elizabeth Bay mansion and never travelled without Bevan the butler or Myrtle the maid, or her chauffeur who wore a silver-grey uniform to match her Rolls Royce motorcars.’

Gladys had no business experience and deferred to Miss Longhurst, whom Huon Hooke describes as ‘stubborn and strong-willed, a woman of some fortitude, but ultimately not very competent… both women lacked lacked vision … and put a dampener (sic) on almost anything new or risky that Max proposed. They treated situations as they thought Frank would.’ Max summed it up this way: ‘The company was being run by a dead man.’

A decade later, Longhurst would ‘carpet’ Max – ‘she tore strips off him for a quarter of an hour,’ Huon Hooke writes, when she found out that he’d ignored her order to stop making Grange. Longhurst also missed the sea change in the market from fortified wines to table wines. The story of Max Schubert and Grange is mostly framed around the challenge he faced making others see the beauty of a new wine style, but Max’s story is really one of a creative genius fighting Penfolds’ incompetent management.

Max goes to Spain

In 1950 Gladys Penfold-Hyland decided to send Max to Spain to study sherry making. Sherry was a popular drink back then, and Gladys wanted Penfolds to make the best Sherry possible. The rest is history: Max going to Spain, then on to Bordeaux where Christian Cruse took a liking to him and showed him everything Max could possibly have wanted to know.

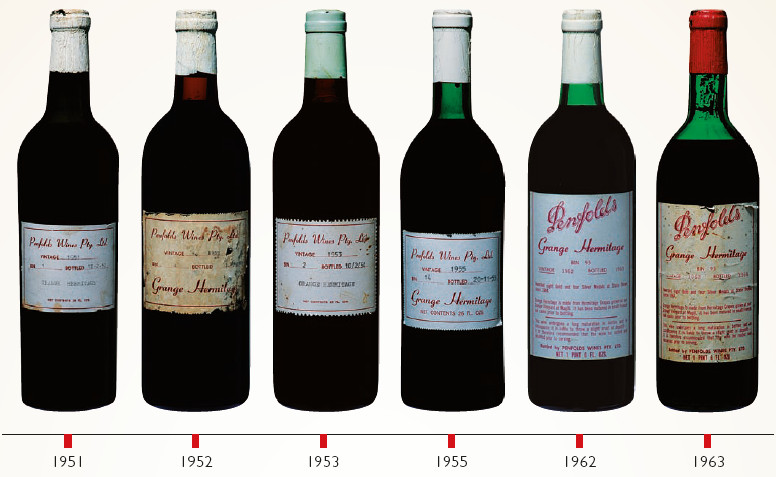

The early reactions to Max’s Grange Hermitage are well-known, along with Penfolds ordering him to stop making the wine in 1957. Maturing reds in new small oak was a pretty radical idea at the time, one that Australian wine judges were simply not used to. What is less well-known is that Max had figured out the importance of long, slow ferments, which he stretched to 12 -14 days from the usual 24 hours of frantic activity. Until then, ferments were a bit like teenage sex: over in a few hasty breaths.

Early Granges. Source: Winestate Magazine

Early Granges. Source: Winestate Magazine

Barossa Bordeaux

Grange often contained 10% or more Cabernet Sauvignon, but Shiraz made up the bulk of the wine since there wasn’t much Cabernet grown in the fifties. Max also preferred American oak to French oak, but he took a leaf out of the Bordeaux book in the way he picked the fruit early – at 11.5 – 12 Beaumé, the equivalent of 12 – 12.5% alcohol in the finished wines.

Max said he wanted to avoid overripe flavours, and that he preferred natural acid to the acid ‘added from a bag,’ (Hooke) so he aimed for natural acidity of 6.5 – 7 grams per litre. Grange is often described as massive and chunky, a brute of a wine, but this had nothing to do with its alcohol level. In my piece Aussie Reds – so much alcohol, so little finesse, I made the point that the early Granges (and Penfolds Bin reds) were often under 13%.

It wasn’t until the mid-nineties that we began to see 14% or more alcohol in these wines on a regular basis (see Addendum below). So what happened in the mid-nineties? Robert Parker the messiah and his gospel of rich, ripe reds – the bigger, the better. John Duval made 14% the norm for Grange, and Peter Gago pushed the alcohol up to the current 14.5% when he took over in 2002. Parker’s Wine Advocate rewarded Gago with a 100% score for the 2008 Grange.

Max set out to make a serious wine that would last 20 years and more. He did that by getting the sugar/acid balance right in the fruit, and by extracting flavour and colour and tannin from skins and pressings and new oak. The more recent custodians of Grange have changed the formula, using much riper fruit and cutting back on the extract and the tannins. I’m not sure that Max would be impressed.

Max’s legacy

Andrew Caillard lists a few of his achievements: ‘Max Schubert and his team pioneered major advances in yeast technology and paper chromatography; the understanding and use of pH in controlling bacterial spoilage; the use of headed down/submerged cap fermentation and the technique of rack and return; cold fermentation practices; the use of American oak as a maturation vessel and perhaps most critically, partial barrel fermentation.’

The submerged cap ferments and daily racking was how Max got so much flavour into his Granges. By using slow ferments lasting 12 – 14 days, he was able to extract the maximum of flavour compounds and grape tannins. New oak barrels added wood tannins as well, and partial barrel fermentation added complexity. Pressings were kept and used for topping up the barrels.

In an interview with Winestate, Max told Peter Simic: ‘The first Granges were made in open fermenters with a false head and the temperature was always controlled during fermentation. I was one of the first to put in refrigeration on a large scale in any winery. And I think I was the first put in a cold room purely for stabilisation purposes. So we were fortunate to have that and it was our policy always to rack the juice every day.’

Fruit selection was also key, and Max chose the best fruit from the best growers in South Australia. Grange was always a multi-area blend, as were most Australian reds of the time. In the Winestate interview, Max said: ‘You cannot make a Grange from just any bloody Hermitage, from any vineyard. You’ve got to be selective. In fact, when I first made Grange I surveyed almost every vineyard in South Australia.’

Huon Hooke makes another point in his book on Max: ‘Many other Australians had travelled to Bordeaux to discover its secrets … David Wynn and Ron Haselgrove were among those paying homage to the great temples of claret in the Medoc. But they did not come home with the gems of insight that Max did.’

Simply put, Max was a better observer and a bigger thinker than the rest. He didn’t just apply his mind to red wine making either: he improved Penfolds Sherries and Ports, and their Brandies. He even introduced pressure fermentation for Penfolds’ Rieslings, and he worked with Ray Beckwith on making pure yeast cultures and matching yeasts to grape varieties.

Underground Grange

In 1957 Max was instructed by Penfolds head office to stop making Grange because the bad reviews were ‘harming Penfolds’ image.’ However, South Australian manager Jeffrey Penfold Hyland backed Max to continue making Grange and told him ‘he’d take the bloody brunt if anything came of it.’ Not much Grange was made in the next few years, and Max couldn’t buy the new oak barrels he needed, but he kept the dream alive.

By then, Max recounted that ‘the older Granges were starting to show out really well and I used to produce them to anybody that came up, and they started talking about them, people such as Max Lake and Doug Lamb. At that time Doug Lamb was a director of Penfolds and he went over to Sydney and laid the bloody law down to the board. He said: “They’re magnificent wines and we should be making more of them.” ‘

The Penfolds board seems to have spent a lot of time asleep at the wheel. In his autobiography Australian Plonky, Ian Hickinbotham recounts how Max talked him into working for Penfolds as their Victorian manager. Even as late as 1965, Ian writes that Penfolds’ management was preoccupied with the dwindling sales of its big seller Royal Reserve Port, and couldn’t see the potential for the wine cask he’d designed.

3 Jimmy Watsons?

From 1962, Penfolds began entering Grange in shows and winning gold medals. Grange took out the Jimmy Watson trophy, not once but 3 times: for the 1963, 1965 and 1967 wines. This proves that Grange wasn’t nearly as hard to appreciate as people make out, since the JW is awarded to one-year old reds at the Melbourne show. The unfamiliar taste of new oak might’ve put people off at first, but by the sixties new wood was becoming fashionable.

In the seventies, Wolf Blass had coined the phrase: ‘No wood, no good,’ and collected 3 Jimmy Watsons of his own. Wolf was another great blender, and used new oak with great skill to soften his reds. Wolf built on the work done by others, although he doesn’t like giving them credit. This interview is typical: it covers Wolf’s life in wine, and he never mentions anyone else by name. It’s as if he’d found the vinous equivalent of terra nullus when he arrived in Australia.

Claims that Wolf used barrel fermentation without building on Max Schubert’s work are hard to believe. ‘Although winemaking at Penfolds had been veiled in secrecy during the 1950s and early 1960s,’ writes Andrew Caillard, ‘many of the ideas were common knowledge by the early 1970s.’

There’s no doubt that Max was out on his own in the fifties, as no one in Australia had experience using new oak in red wine making. Max had to figure it all out for himself, and some say that was his true genius.

Different Styles

Looking at Penfolds’ 3 Jimmy Watson winners, we find their alcohol and pH levels a little higher than expected, and that may have something to do with their appeal as young wines (and the judges may have wanted to make up for their past mistakes as well). These were probably warm vintage years as well, and in those days wines tended to reflect that more.

· 1963 – Total acids: 6.7 grams per litre, pH: 3.60, alc. 13.3%

· 1965 – Total acids: 5.9 grams per litre, pH: 3.68, alc. 13.2%

· 1967 – Total acids: 5.8 grams per litre, pH: 3.62, alc. 12.7%

Max didn’t set out to make reds for early consumption, while Wolf Blass did – he aimed for higher pH levels of 3.8 – 3.9, and lower total acidity. At the 1974 Jimmy Watson Trophy award ceremony, Wolf Blass famously said: ‘My wines are sexy – they make weak men strong, and strong women weak.’ To add insult to injury for Wolf’s critics, his wines have lasted much longer than they predicted.

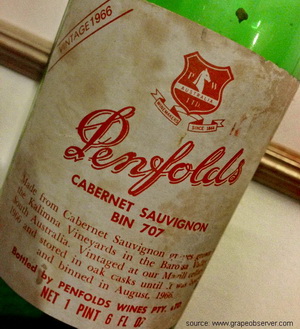

The Children of Grange

Ian Hickinbotham said Max wanted Penfolds to put more effort into promoting the bin reds he’d created. The company was lucky Max didn’t turn his back on it, but his loyalty was unwavering. By the early sixties, Max had learned enough from Grange making to produce a range of reds that were to become the envy of Penfolds’ competitors: Bin 389 Cabernet Shiraz, Bin 707 Cabernet Sauvignon, Bin 28 Kalimna Shiraz, Bin 128 Coonawarra Shiraz and Bin 2 Shiraz Mataro.

Bin 389 became known as ‘the poor man’s Grange’ since it shared some of the goodness in a softer envelope at a more affordable price. Rumour had it that Bin 389 was matured in the barrels Grange came out of. Where did all the Cabernet come from all of a sudden? Cabernet was the fashion grape of the late fifties/early sixties, and there was a mad rush to plant more of it. The red wine boom was off and running.

I have an old price list from 1966, which lists both Grange 1960 and St Henri 1961 at $1.75. Rouge Homme Cabernet 1961 wasn’t far behind at $1.65. The most expensive wine on the list is Mildara’s 1963 Coonawarra Cabernet at $1.85. The Penfolds bin reds aren’t listed but they would’ve been just over a dollar, on par with Chateau Reynella Claret and Metala Shiraz Cabernet.

That St Henri was the same price as Grange in those days is fascinating, but these were the company’s top reds at the time – the old and the new, one made by John Davoren along traditional lines, the other by Max Schubert.

Penfolds’ Vinyards

While Penfolds had longstanding supply arrangements with growers in South Australia, the company also owned a bunch of vineyards: Magill, Auldana, Kalimna, assorted vineyards in McLaren Vale, Coonawarra (planted in the sixties), Minchinbury (now a housing development in western Sydney), half the Dalwood vineyard at Branxton, the Wybong vineyards in the upper Hunter (planted early 1970s), and a vineyard in the Polish Hill region of the Clare Valley (planted in the eighties).

While Penfolds had longstanding supply arrangements with growers in South Australia, the company also owned a bunch of vineyards: Magill, Auldana, Kalimna, assorted vineyards in McLaren Vale, Coonawarra (planted in the sixties), Minchinbury (now a housing development in western Sydney), half the Dalwood vineyard at Branxton, the Wybong vineyards in the upper Hunter (planted early 1970s), and a vineyard in the Polish Hill region of the Clare Valley (planted in the eighties).

John Lewis wrote in the Newcastle Herald about a 1973 Penfolds Dalwood Pinot Riesling he came across, which turned out to be a Chardonnay-Semillon blend. The Chardonnay (thought to be Pinot Blanc at the time) was sourced from the HVD vineyard Penfolds bought in 1948. Murray Tyrrell rated it one of the finest vineyards in the Hunter and the story goes that, on a moonlit night in the late sixties, Murray jumped over the fence and purloined some Chardonnay cuttings from it.

Max played a leading role in the management (and planting) of these vineyards (he was a workoholic), including the Polish Hill venture which is remembered by very few people. Andrew Pike (now of Pikes, then Penfolds vineyard manager) helped select and plant the vineyard to Cabernet, Cabernet Franc, Merlot and Malbec. Max must’ve had a dream to make a Bordeaux blend after all; he even made sure the wine was matured in French oak.

I bought Penfolds Clare Estate reds (no bin number) in the early nineties, and enjoyed a number of elegant bottles from the 92, 93 and 94 vintages. They were very different from the other Penfolds reds. Sadly, Penfolds stopped making the wine after Max died.

Today’s Bin 389 is far from a poor man’s bottle of wine with a price tag of $70, Bin 707 is almost $300 and Grange has established a firm place in the luxury goods market with a price that’s heading for $1000. TWE has decided to squeeze Max’s legacy for max profit, and has created an ‘icon’ range of bin reds around the pedestal occupied by the masterpiece.

As long as the Chinese buy these creations of Penfolds haute couture, TWE will keep cranking up the prices. Just remember our advice in Penfolds Grange – rich wine, poor investment: you can buy Grange much cheaper (and older) at auction than on release.

One man against the world

What Max Schubert would make of all this we’ll never know. What we do know is that the Australian wine industry owes Max a huge debt of gratitude. Max wasn’t a renegade, and not that much of a maverick either, but he was a pioneer who observed and learned and wasn’t afraid to experiment or to back his judgement.

Max was also a natural manager who understood how to get all those in his sphere of influence to give their best, by making them feel an important part of the team. Huon Hooke tells us in his book on Max that, under Leslie and Frank Penfold-Hyland, it was management by fear that pitted one winery against another.

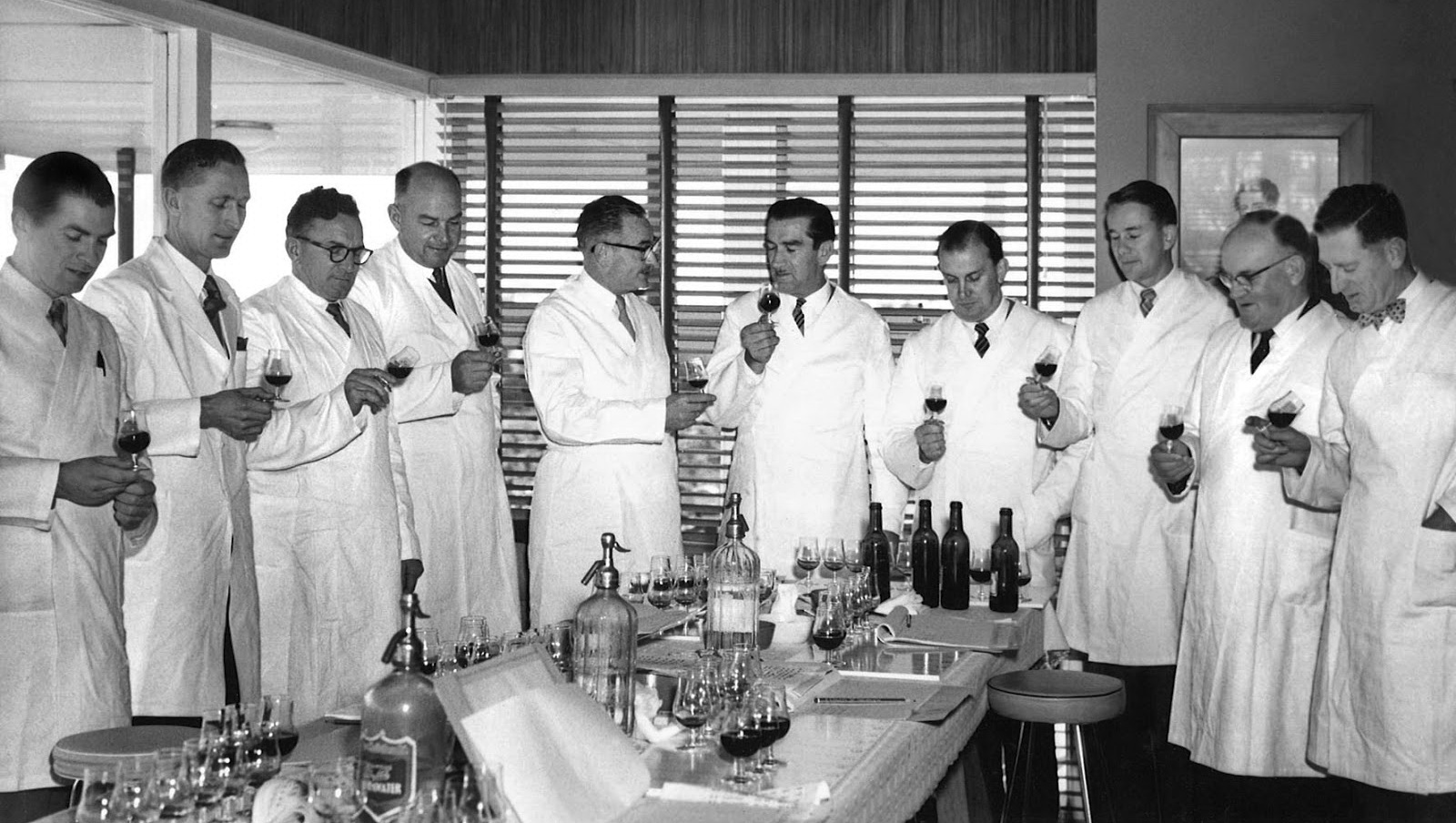

After the disastrous ‘petticoat government’ of the fifties, Jeffrey was the last Penfold-Hyland left standing and moved from South Australia to Sydney to take over. Jeffrey was Leslie’s son and had inherited his father’s flair but lacked his business acumen, according to Huon Hooke. Jeffrey wasn’t admired by anyone but Max Schubert who was very close to him. (Jeffrey is standing on Max Schubert’s left in the photo below. Click on the image to see a larger version).

The Penfolds team in the fifties. Left to right: Murray Marchant, Gordon Colquist, Ivan Combet (father of former Cabinet Minister Greg Combet), Perce McGuigan (father of Brian and Neil), Jeffrey Penfold-Hyland, Max Schubert, John Davoren, Don Ditter, Harold Davoren (John’s father) and Ray Beckwith – photo credit: Milton Worldley

The Penfolds team in the fifties. Left to right: Murray Marchant, Gordon Colquist, Ivan Combet (father of former Cabinet Minister Greg Combet), Perce McGuigan (father of Brian and Neil), Jeffrey Penfold-Hyland, Max Schubert, John Davoren, Don Ditter, Harold Davoren (John’s father) and Ray Beckwith – photo credit: Milton Worldley

The world falls apart

By the early seventies, Penfolds was in a sorry state: the company was badly run, it had made some bad investments in New Zealand, it had run up debts, and it had missed the big swing in the market to white wine. When Jeffrey Penfold-Hyland appointed director Bill Weir to the MD role in 1973, things went from bad to worse.

Weir did such a bad job from all accounts that everyone thought he was trying to make the company a cheap takeover target. Max soon found himself on the outer, while younger guys like Chris Hancock enjoyed a fast climb up the ladder of success. During this time, Jeffrey had a nervous breakdown and Max’s health suffered badly. (Hancock joined Rosemount in 1975 and ended up running the business).

In the same year, Bill Weir announced Max Schubert’s retirement at a wine conference in Adelaide, and wished him well. It was the first Max had heard of it. Was this the shabby treatment Richard Farmer talks about? No. According to his brother David, that happened in the late 1980s at a testimonial dinner. David adds that Max was entitled to an annual case of Grange but had to pay for it.

Back in the late seventies, Jeffrey fired Bill Weir eventually and sold Penfolds to Tooth and Co. The brewer bought the family’s 51% shareholding for less than $8 million, a ludicrous sum. The company’s liquid assets alone were worth more than that, let alone all the vineyards, wineries, offices and warehouses.

Max told Huon it was a good thing, and said Tooth & Co got rid of some dead wood and cleaned things up in general. He was less impressed when they decided to discount Grange and the other top reds, in order to reduce the vast stocks of red wine that were sitting in the company’s cellars.

Bottles and barrels of Grange maturing at Magill Cellars

Bottles and barrels of Grange maturing at Magill Cellars

Penfolds forever

Max never retired but stayed on as a director and consultant, working from an office at Magill. He stayed through the grim days when corporate raider Adsteam bought Tooth & Co, and John Spalvins sold most of the vineyards around Magill to developers. ‘Spalvins wanted it all to go,’ Max told Huon. ‘He would’ve liked to raze the buildings as well.’

Barbarians at the gates. Of course there was a public outcry and lots of community protests, but eventually all but 5 of the 120 hectares were developed for housing. This had little impact on Grange, which rarely contained fruit from the ‘Grange’ vineyard anyway. From 1983 on, Max used the fruit for a new wine label he created: Penfolds Magill Estate.

Max Schubert’s enormous contribution to Penfolds took time to be recognized. In 1984, he was awarded an AM for services to the Australian Wine Industry; he was Decanter magazine’s ‘Man of the Year’ in 1988, he won the inaugural Maurice O’Shea Award in 1990 and received an Australia Day Citizen Award in 1991.

Max was gracious enough to give others plenty of credit. In a paper he delivered at the first Australian National University Wine Symposium in 1979 in Canberra, Max told his story of Grange making and ended with these words:

‘I wish to pay tribute to the many winemakers, technicians, cellar managers, senior cellar hands and vineyard supervisors who, over the years, so ably assisted me in the making of Grange. Each one had a part to play in every vintage made, and even though I always retained absolute control of all stages of Grange production and, indeed, company production generally, without their help, support, interest and co-operation, it would have been almost impossible for me to cope, particularly in the later years before my retirement in 1975.’

Kim

Addendum

This list shows how the alcohol level in Grange climbed over the years. It also shows that there was often more than 10% Cabernet in the famous Hermitage (up to 15% is legal under our system). It’s interesting that the figures for the 1976 are pointing toward Wolf Blass, and I declared this the perfect Grange at a tasting last year, the best I’d ever drunk. Today’s auction price for the 1976 ranges from $540 to $700 (depending on condition).

1971 – 12.3%

1972 – 12%

1975 – 13.4%

1976 – 13.9% – 89% Shiraz & 11% Cabernet Sauvignon; 5.1 grams per litre, pH: 3.73

1978 – 12.9%

1981 – 12.6

1984 – 13.6

1986 – 13.7% – 87% Shiraz & 13% Cabernet Sauvignon. 7.1 grams per litre, pH: 3.41

1988 – 13.5%

1993 – 13.5%

1996 – 14% – Total Acidity: 7.20g/L, pH: 3.41

1998 – 14.5%

2000 – 14%

2002 – 14.5%

2004 – 14.5%

2006 – 14.5%

2008 – 14.5% – Total Acidity: 7.0g/L, pH: 3.48

Additional reading

Penfolds Max’s Collection – Trashing a Great Australian’s name for a fistful of dollars

Ray’s own 100th birthday speech and who really employed Max Schubert

Penfolds releases £1.2m vertical Grange collection

What Penfold’s Grange can teach us about craftsmanship and perfection