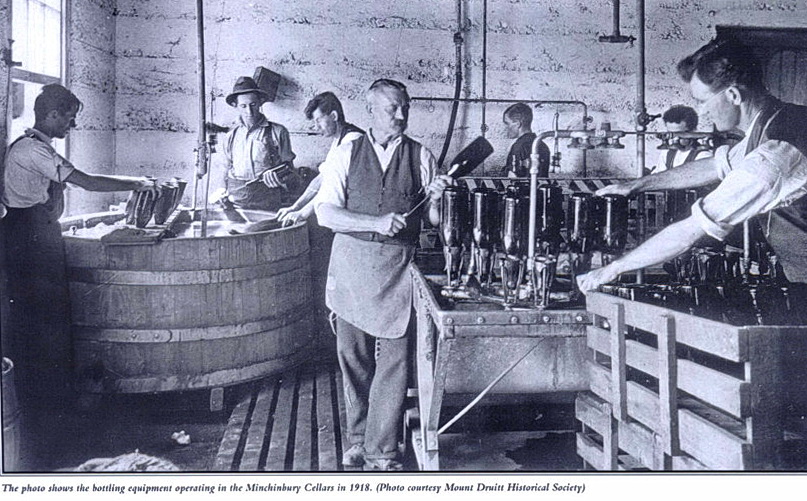

what else can we do?

Where the Streets have Hallowed Names

On a recent Sunday outing we decided to visit Minchinbury, which is now a Sydney suburb between Mount Druitt and Rooty Hill. We were astonished how little was left of the Penfolds winery that once produced one of Australia’s top sparkling wines. So much history here, and so little to remind us of it apart from a few streets in the neighbourhood with random wine names like Burgundy Place and Barossa Drive, Combet Place and Buring Crescent.

The site is now a housing development with a restaurant and a small museum (pictured), which wasn’t open on this lovely autumn Sunday and didn’t look as if it had been open recently. The people in the nearby restaurant knew nothing about it. There is a ‘Heritage Walk’ around the perimeter of the site, with signs that remind us of the buildings that once stood here. An old chimney around the back looks as out of place as a Roman column on a Harry Seidler building.

The Short Story

After World War II, Penfolds had 100 ha under vine at Minchinbury. In the sixties, it began to sell off some of the land to developers as Sydney’s urban sprawl pushed relentlessly west. ‘By 1973 a little under 14 ha remained,’ James Halliday tells us, ‘gewurztraminer accounting for half, along with riesling, trebbiano and some chasselas.’ It was the Traminer and Riesling which made Penfolds fabled Trameah, and later the Bin 202 Traminer Riesling.

Penfolds sold the site in 1978 and, despite its historical significance, Landcom and L.J.Hooker planned to develop it for housing. There were delays and, four years later, vandals set fire to the site destroying everything except the concrete and brick walls, that chimney and the corrugated iron tower that houses the museum.

The site was sold to another developer who did nothing, and it deteriorated further until Minchinbury Winery Estate Developments Pty Ltd bought it in 2010 and built 10 townhouses and 45 units on it. The company says it spent over $2m on the restoration of historical aspects on the site. Some of the original walls of the old building were included in the design, and the cellar was turned into a gym and pool for the residents. More details HERE.

The real story

Most of us think of Penfolds as a thoroughly South Australian wine company, yet for many decades most of its vineyards were in NSW: Minchinbury on the outskirts of Sydney, and Dalwood, HVD and Wybong in the Hunter. The company’s headquarters were in Sydney as well, on the Princess Highway at Tempe where a big old barrel stood like guardian out front.

Frank Penfold Hyland bought the Minchinbury vineyards and cellars in 1912, and put Leo Buring in charge. Buring had been making wine at the Minchinbury cellars since 1902. He had trained at Roseworthy, at Geisenheim and at Montpellier. Buring had worked in the Hans Irvine wine cellars at Great Western (later acquired by Seppelt), and had begun making sparkling wine at Minchinbury. Buring left Minchinbury in 1919 and became a consultant to other wineries until he set up his own business in 1931: Leo Buring Pty Ltd.

A Love Story

Greg Combet’s father and grandfather worked at Minchinbury as winemakers, and Greg grew up on the estate where his family lived in a cottage provided by Penfolds. The story of the Combet family is a fascinating one, recalled by John Lewis at the Newcastle Herald in 2007.

Lewis tells us that the story ‘involves a French seminarian and a nun who ran away to marry in Australia, one of the Hunter Valley’s greatest vineyards and the high-profile master tactician of the nation’s peak union body, ACTU secretary Greg Combet.’

The story tells how Greg’s great grandfather Alex and wife Marie Antoinette came to Australia from France, where Alex was a Catholic seminarian [and assistant altar wine maker] and Marie Antoinette a nun. They fell in love and left their respective orders behind, married in Maitland in 1902 and lived at Allendale. Alex became the manager of the new Hunter Valley Distillery venture a few years later.

‘As the HVD venture got under way in 1908,’ Lewis writes, ‘it seems likely that Alex Combet oversaw the planting of HVD vineyard to chardonnay, semillon, clairette and trebbiano vines. Grapes from the vineyard and surplus fruit bought from other winegrowers were used to run the HVD distillery, which was built near the Allandale rail underpass.’

From Maitland to Minchinbury

‘When I was born in 1958,’ Greg Combet wrote in the Sydney Morning Herald, ‘my father Ivan Louis Combet, known as Tod, was a winemaker at Minchinbury. We – my father, mother, older sister Jennifer and I – lived in a cottage just inside the arched entrance on the Great Western Highway. I spent the first 13 years of my life growing up on Minchinbury, roaming the property and wandering through the estate. An abiding memory is the smell of the winery, the yeast, the fermentation of grapes.’ More HERE.

Alex’s son Ivan went to work for Penfolds at Minchinbury in 1919, and became wine and champagne maker-manager there. He was succeeded by his son Ivan (known as Tod) in 1967 but Tod Combet died of bowel cancer in 1971 at the age of 44. Like his son Greg, Tod was born on the estate. After his death, Greg’s mother was given six weeks to move out of the cottage. Greg was just 13 at the time.

The Bigger Story

Penfolds was a land of giants, from Leo Buring and Max Schubert to John Davoren (the father of St Henri) and Don Ditter. Ray Beckwith was the first wine chemist in the country who understood the crucial role pH played in preventing bacterial spoilage, which nearly destroyed Penfolds in the thirties. In those days almost every second bottle of wine sold in Australia was made by Penfolds, and most of it was fortified. Ray Beckwith lived to 100 years of age.

In many ways, the story of Penfolds is the story of Australian wine. The genteel old family wineries with household names were utterly unprepared for the corporate raiders who charged across the land in the seventies and eighties like hordes of barbarians. Penfolds, Seppelt, Lindemans, Wynns and many more were pillaged in a frenzy of corporate greed. More HERE.

A decade later, Southcorp bought most of the great brands from corporations who couldn’t remember why they’d ventured into the wine business. Then Southcorp fell victim to the same greed and paid $1.5 billion for Rosemount. The company’s digestive system failed to cope with the expensive meal and eventually collapsed. In 2005 Southcorp was bought up by Fosters, which floated the wine business off as Treasury Wine Estates in 2010 because it was ‘a distraction to the beer business’ the company sold to SA Brewing a couple of years later.

Max Schubert was far more than the father of Grange. With the help of the brilliant chemist Ray Beckwith, he cleaned up Penfolds’ production and rationalised the company’s vineyard holdings. You can read the gory details in Max Schubert, Ray Beckwith and the Making of Penfolds, where I try to set the record straight. Max kept making great wines while the ‘petticoat government’ in Sydney was busy running the great company into the ground. Huon Hooke’s book Max Schubert, Winemaker offers some wonderful insights, but it’s no longer in print.

Penfolds treated Max as badly as they treated the Combet family. Max got a Citizen watch when he retired in 1975 and was entitled to buy a case of Grange every year. Yes, BUY. Max had spent his entire working life at Penfolds, just like Greg Combet’s father and grandfather at Minchinbury.

Kim