The Stakes for Cellaring Classy Reds have been Raised

‘Later picking – sometimes even after the Sauternes harvest in October – was becoming more common,’ Professor Denis Dubourdieu told Decanter a couple of years ago. He added: ‘There is a race towards concentration, to please many critics . . . ‘I have been a consultant for 30 years; I have spent the first 20 years telling people not to harvest too early; in the last 10 years I have told them not to harvest too late.’ More Here.

Bordeaux greats past their prime at 10 years of age?

I’ve expressed my distaste for super-ripe, high-alcohol reds before in Aussie Reds – so much alcohol, so little finesse, but the focus of this piece is on the cellaring potential of this style. In a recent Decanter article, Jane Anson talks about ‘a wine crisis hiding in plain sight,’ as she reports on a tasting of Bordeaux classed growths from the 2003 vintage. ‘Even among the biggest names there were bottles that were showing tired fruit, flabby structure and were generally past their prime,’ she writes, ‘all signs of oxidative destruction that is not expected at such an early stage in the life cycle of fine red wine.’

2003 experienced unusual heat during the growing season, but 2009 and  2010 also produced very ripe, high-alcohol reds in Bordeaux. Many are 14.5 and even 15%, and these are often wines Robert Parker rates at a perfect 100. Some say Parker has a lot to answer for, since he’s used his enormous influence to promote monster wines. Others say winemakers didn’t have to follow Parker.

2010 also produced very ripe, high-alcohol reds in Bordeaux. Many are 14.5 and even 15%, and these are often wines Robert Parker rates at a perfect 100. Some say Parker has a lot to answer for, since he’s used his enormous influence to promote monster wines. Others say winemakers didn’t have to follow Parker.

Precedent: Premature Oxidation in White Burgundies

Some winemakers haven’t, but most have in order to shift their expensive bottles. Denis Dubourdieu was one of the team that led a groundbreaking study into premature oxidation in white Burgundy wine in the early 2000s. He told Jane Anson that nobody wanted to talk about it when it was first discovered, and adds: ‘I believe there is a similar scandal with red wine, and that in 10 years’ time it will be just as explosive as the one affecting white Burgundy has been. And it’s not limited to one region but all red wines that are expected to be aged for long periods of time – so Barolo, Napa, Bordeaux, the Rhône, Burgundy and others – are in danger of ignoring this threat.’

The premox issue in white Burgundy was most obvious in wines from the 1996, 1999 and 2002 vintages, and reasons given ranged from changes in winemaking techniques to faulty corks to global warming. The real reasons still elude the experts but more remarkable is the observation by some in the trade that these wines can perform a Jekyll & Hide change in the glass in front of you. That smacks of Burgundian propaganda designed to keep you buying their even more expensive bottles …

The blush of youth hides many faults

With reds, the problem is much broader than Bordeaux. If you’ve drunk Cote-du-Rhone over the years, you might recall that this was a light red style in the same weight class as Beaujolais. Now you’re likely to get a 14.5% heavyweight that has lost the spice and fragrance this style once offered in abundance. Aussie reds have followed the same trend, of course. The question is: what will they look like after a decade in the cellar?

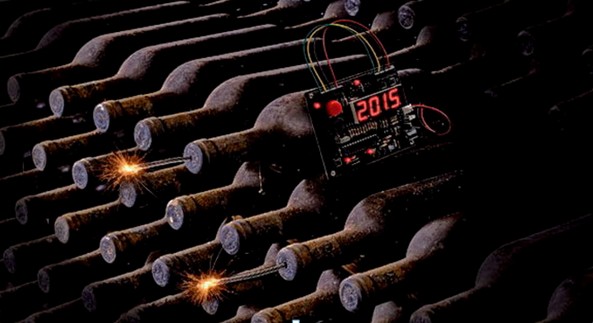

No one in the wine business would argue that it’s easy to assess the cellaring potential of wines, and young reds can be especially tough because there’s a lot going on that can cloud your faculties. In addition, wines can change in unexpected ways over 10 – 20 years in the cellar: you can end up with a tannic monster with all the fruit dried out, or you might have a perfectly balanced wine. The only thing we’re sure about is this: if a wine is out of balance in its youth, time in the cellar will not fix it.

Reds are more complex

Old style Aussie reds were dense young things with subdued fruit and a fair whack of acid and tannin. New style reds are richer, ripe and softer, with much less acid and tannin. That makes them easier to like when they’re young, but it doesn’t make them good cellaring propositions. The Kalleske Moppa Shiraz 2010 we had last night was barely 5 years old and ready to drink, no point keeping it. An Evans & Tate Metricup Road Cabernet Merlot 2009 we opened a few days before would’ve been better a couple of years ago. A Wendouree Cabernet Malbec 1993 we drank a month ago was a Peter Pan of a wine, and I wouldn’t hazard a guess how much longer it will take to grow up.

Bordeaux’s grand vins are collected and bought and sold over many years, and are expected to improve for a couple of decades or more. They need a pretty solid backbone to do that, but you won’t find that in most super-ripe reds. Sugar and acid are like a push-me, pull-you: when one goes up, the other goes down.

In Bordeaux, Merlot has grown in popularity because it ripens earlier and adds a soft side to the stern Cabernet. Didier Cuvelier, owner of Chateau Leoville Poyferre in St Julien, told Decanter that the Merlot these days was ‘so high in alcohol that we run the risk of losing the Bordeaux style.’ Consultant Jean Claude Berrouet, formerly at Petrus, says in his 40-year career he has seen alcohol rise between 2 and 2.5 degrees [in red Bordeaux].

What happens inside the factory?

Inside the grape, in this case. The sugar level determines the alcohol and natural acidity of a wine. Phenolics determine a wine’s colour and flavour compounds, and its grape tannins. Sugar and phenolics advance along different maturing curves: in hot climates like ours, phenolic ripeness tends to lag behind sugar ripeness. In cold climates like Germany’s, it’s the other way round. In perfect climates, the two curves intersect for perfect physiological maturity.

In a year such as 2003 in Bordeaux, the weather got so hot that that many of the vines simply shut down. That meant phenolic ripeness was lagging behind the sugar levels which had already shot up, and this made physiological maturity difficult to achieve. The resulting reds will show characters ranging from stewed prunes to dried figs.

3-methyl-2,4-nonanedione

We first encountered the stewed prunes character in Lindeman’s reds from Coonawarra. In a piece called The Puzzling Problem of Premox, Tyler Coleman refers to a 2008 study by Alexandre Pons et al which identified the compound responsible for an ‘intense off-flavour reminiscent of prunes’ in prematurely aged red wines as 3-methyl-2,4-nonanedione, or MND for short. There you go.

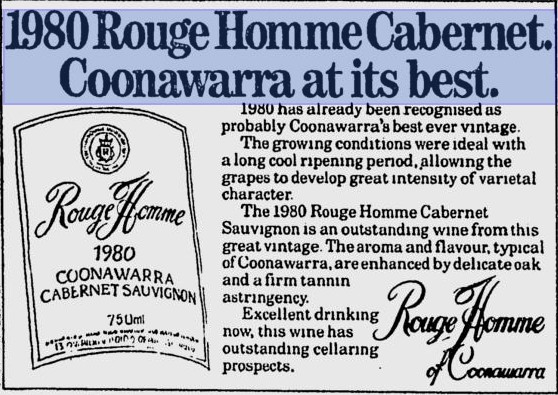

In a young red, this character can be quite seductive, and I remember being the odd man out (with one exception) in a group of seasoned tasters who all loved the wine – a Rouge Homme 1980, from memory. Tasting the same wine again with the same group some years later was a sweet kind of revenge, as they turned up their noses at the very obvious stewed prunes character.

pH – the bottom Line

Changes in winemaking also play their part, most of all the micro-oxygenation now used widely to soften the wine and to heighten the fruit expression. Even when this is done under strictly controlled conditions, the practice allows the wine to come into contact with more oxygen. Not so long ago, winemakers used to do everything in their power to prevent that. It comes back to pH in the end, and I thought it would be interesting to check these values in the Bordeaux reds of 2009 and 2010.

The Wine Cellar Insider reviews a bunch of 2009 Bordeaux reds here, and writes: ‘While it’s high in alcohol (14.2%), it has no sensation of heat. Another interesting statistic … is that the 2009 Haut Brion shows a high pH level, 3.9, yet the wine displays ample freshness.’ This is what I mean by the blush of youth masking long term issues: ideally the pH of the grand vin should be between 3.2 and 3.6, and the alcohol less than 14.2.

One of the first oenologists in the world to recognise the importance of pH for wine quality and for prevention of bacterial spoilage was Alan Hickinbotham (he ran the first oenology course at Roseworthy college). Ray Beckwith studied at Roseworthy and joined Penfolds in 1935, where he pioneered practices that solved a lot of spoilage problems that dogged Penfolds at the time. Ray became the guy in the lab Max Schubert relied on when making the early Granges. More in Max Schubert, Ray Beckwith and the Making of Penfolds.

As I show in the piece on big Aussie Reds, Grange and St Henri used to be around 13% alcohol or less until the 1980s, when others took over wine making from Max Schubert. It wasn’t just Penfolds: between 1984 and 2004, average alcohol levels in Aussie red wines rose from approximately 12.3% by volume to 13.9%, and they haven’t stopped going up yet. So how well are these big reds going to cellar?

Kim