The Gold Rush

Australian wine had a heyday in the latter part of the 19th century, when the gold rush brought all kinds of adventurers to this country. Boat people, migrants, refugees. They came from the old world and the new (America). They were seekers of fortune, followed by entertainers, suppliers of mining needs, cooks and market gardeners.

Melbourne was the hub of the gold rush, a bustling city where Bohemians entertained the masses in the lavish theatres that sprang up, where restaurateurs catered for their appetites, and where wine flowed easily. Australian wine triumphed at the great exhibition of 1888, at the magnificent new Exhibition Centre in Rathdowne Street. Victorian wines won medals against all comers, wines from Great Western and Bendigo and Geelong.

Depression

The depression of the nineties saw a return to a simpler life for most Australians, where survival was the order of the day and food and wine took a back seat. Little changed through the first decade of the new millennium, and the second that saw the Great War as they called it. By the end of the third decade, things began to look up, but then the sky fell in on the stock market, the Great Depression followed, and yet another Great War.

If that wasn’t enough, the wowsers in Australia tried to close down the whole drinking business. Six o’clock closing was a bad compromise that lasted until the early sixties. Instead of moderating drinking habits, the temperance movement created an early wave of binge drinking: the ‘six o’clock swill’, where men gathered in pubs after work and tried to drink them dry before they closed.

Fortification

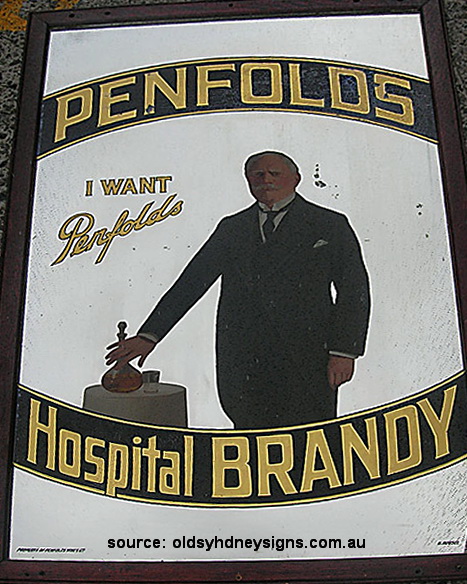

For the first half of the 20th century, winemakers from Coonawarra to the Hunter Valley survived by turning much of their fruit into Brandy, Sherry and Port. Brandy was respectable when labelled Hospital Brandy, since some marketing genius had attributed restorative powers to it. Much of Australia’s Sherry and Port ended up being drunk in dingy bars, until the fifties when Sherry became popular as a late afternoon tipple with the ladies.

Table wines were a rarity because drinking wine with food had become a vague memory from a bygone era to which most people had lost the link. Lindemans, Leo Buring and Johnny Walker in Sydney, and Doug Seabrook and Dan Murphy in Melbourne, sold fine table wine to a tiny niche market of died-in-the-wool connoisseurs.

Bubbles save the day

In the early fifties, the Germans come up with several new technologies that revolutionised white wine making:

- Fermentation in pressure tanks produced much fresher, more aromatic wines

- The Charmat process, which used pressure tanks for secondary fermentation, retained the bubbles formed by the CO2 released and opened the door to mass producing cheap bubbly.

- The final link in the chain was the semi- automatic sterile bottling plant that guaranteed that white wines reached consumers with all their new-found freshness intact .

Colin Gramp at Orlando and Rudi Kronberger at Yalumba seized the day, and a new style of Riesling was born. I remember the first time I drank a half bottle of Orlando Riesling in the restaurant of the Hotel Canberra in the early seventies: it made me an instant fan of South Australian Riesling, and I’ve never looked back. In the fifties, almost no one drank Riesling so Colin Gramp looked for another avenue to make a return from his surplus of grapes.

Pearls of wisdom

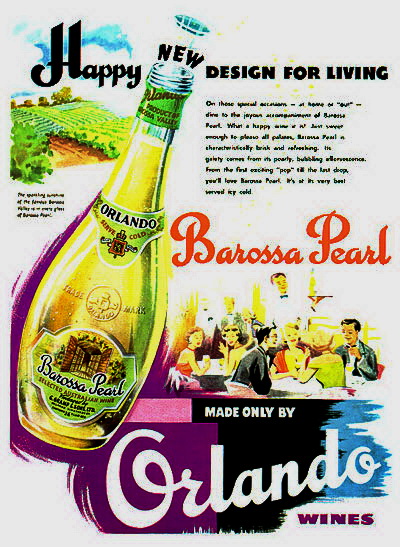

Colin saw the Germans making large volumes of Perlwein with the Charmat method, and making large amounts of money in the process, so he brought out the pressure tanks and the bottling lines and a fellow called Gunther Prass who knew how to make Perlwein. Orlando’s version was to be a light, delicate, fruity wine with a clean, lingering finish. It was packaged in a Perrier-style bottle with a longer neck.

Barossa Pearl didn’t make the target release date – the Melbourne Olympics – but was released on Guy Fawkes’ Day, and was an instant success. Bottles sold in the millions and then in the tens of millions, making a lot of money for Orlando which Colin Gramp invested in bold experiments like the Steingarten vineyard high above the Barossa.

A clever aside was Orlando’s use of Muscatel and Frontignan juice in the secondary fermentation, instead of sugar. ‘By adding a quantity of juice,’ Colin Gramp later told historians Rob Linn and June Edwards, ‘you broke back your alcohol … and of course, using varieties such as Muscat and Frontignan, you obtained that fruitiness in the wine.’

With one masterstroke, Orlando had produced a wine that had broad appeal, and one people could drink a lot off without falling on their faces. Genius.

The Pearl Wine Wars

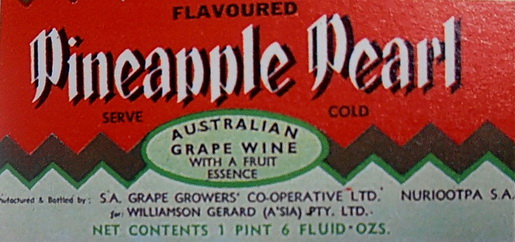

Ian Hickinbotham over at Kaiserstuhl saw Perlwein as a way to shift the vast surplus of grapes in the ailing growers’ co-op he was trying to make profitable. He couldn’t afford to buy the fancy German equipment, so he built his own and hired a young winemaker called Wolf Blass in 1961. Wolf has been on the radio a lot in the last year or two, talking about how he showed Australians how to make table wine, but that’s another story.

He did the job for Ian Hickinbotham with such awful creations as Pineapple Pearl. ‘It came in a pineapple/hand-grenade-shaped bottle,’ recalls Philip White, ‘with a lurid green plastic emulation of the crown of the pineapple around its stubby neck. Last time I was pleasured to visit Blass at his home, he still had a row of these proudly displayed along the shelf atop his bar.’

Then White adds this interesting twist: ‘The advancements Hickinbotham made in sparkling wine manufacture soon had Kaiser Stuhl making enormous volumes of wines for its rivals. He saved his growers. Penfolds, Seppelts, Yalumba and many merchants all over Australia were soon depending on Kaiser Stuhl for their sparklers; even the phenomenally-successful Leo Buring Sparkling Rinegolde came from Kaiser Stuhl.’

Some of these were still going strong in the late sixties – I remember being offered Lindemans Porphyry Pearl at a party in Paddington. These sweetish bubblies were big hits with the ladies, while most of the blokes hung onto their Resch’s DA.

WOGS

We were still a long way from drinking wine with meals – Perlwein was mostly a party drink. It was the Italians and Greeks, and the Germans and other Europeans, who re-introduced Australians to the delights of good food and wine. Remember, Australian cuisine had fallen to a rock bottom where roast lamb and three veg was a degustation meal, and roast chicken a Christmas feast.

I remember working at Olivetti in the mid-sixties in East Sydney, with some young Italian guys who would occasionally talk us into having lunch at La Veneziana, a cheap Spaghetti joint just up Stanley St from Beppi’s (one of the first ‘serious’restaurants in Sydney after the war). Of course we drank a glass or two of rough Fiorelli red with our Spag Bol, and thought it was all very civilized.

Gas Bags

The sixties were a time of prosperity, and lots of people developed a keener interest in food and wine. They took flagons home, at first, so there was always a glass of wine handy, but it was the cask that made wine a beverage that was always on tap and always fresh.

Tom Angove was the first to come up with the bag-in-the-box idea, but couldn’t make it work without leaking. I remember a wine writer friend pouring me a glass of awful white wine out of a gallon Penfolds metal cask made to look like a wine cask. It leaked as well. In the end, it was Wynns who perfected the design and used the proceeds to invest in the ambitious Mountadam vineyard.

Len Evans did his bit to educate the punters, of course, but he warmed up a different audience at Bulletin place: Business and inner city types. And Bohemians – yes, theatre was back in fashion as well, and there was a mining boom in the late sixties. History repeats itself, ja? It was a generation change, and by the early seventies, having a glass of wine with lunch or dinner had become the norm once more.

Kim