The story of the wine merchants who turned a country of beer and sherry drinkers into lovers of fine wine

The first half of the 20th century saw dramatic changes in the way Australians lived. The gold rush of the previous century had attracted hordes of fortune seekers to Victoria, and Melbourne had become a thriving metropolis that dished up exotic food and wine and all kinds of entertainment. The Great Exhibition in Melbourne in 1880 was the crowning glory that celebrated Australia’s diversity and sophistication.

By the Fin de Siècle, there was a distinct feeling of the morning-after – the economy had stalled, there had been a run on the banks, and many saw this as punishment for previous excesses. The two world wars and the great depression in between had made survival a priority for most Australians. There was no room for fancy things like gourmet food and wine.

The wowsers and the 6 o’clock swill

There was no room for immigrants either – the only winners were the wowsers. The temperance movement was run by women determined to stamp out the demon drink. They almost succeeded, but a compromise was reached with the 6 o’clock closing of pubs. The barbaric six o’clock swill was abolished in Sydney in 1955, but lasted another 11 years in Melbourne.

Wine companies took to promoting the health and medical benefits of their wares – hospital brandy etc. Virtually all wine and brandy was sold by hotels. There were no independent bottle shops and few wine merchants. Wine bars were dingy places avoided by self-respecting citizens.

Restaurants were few and far in between, and most families ate simple meals at home. Corn beef and three veg, that kind of stuff. Real men drank beer, and women drank a sweet sherry here or there. ‘Although the industry limped along on exports,’ writes historian David Dunstan, ‘by the 1960s this overseas market was almost dead and Australia had become a byword for everything execrable in wine.’

The Turning Point

I suspect David exaggerates, but there’s no doubt that our wine industry was on its last legs ten years earlier. A few wineries had toughed it out in the Barossa, Rutherglen and the Hunter Valley. Of course there were people who drank table wine during the war years and the depression – doctors, lawyers, academics and other professionals – but their number was small.

A little known fact industry veteran Al Hill shared with me is that wealthy graziers were among those who drank good table wines. They learned about refined dining and drinking on their trips overseas to the UK and the Continent as it was called then. Back home, companies like Dalgetty would import wine for their grazier clients because no one else did.

The Wine & Food Societies in Sydney and Melbourne were founded in the late 1930s, and thrived after WW II. Immigrants from Europe brought their eating and drinking habits with them, but the Italians and Greeks mostly made their own wine. Still, Australia’s few table wine lovers could sense an upturn in their fortunes.

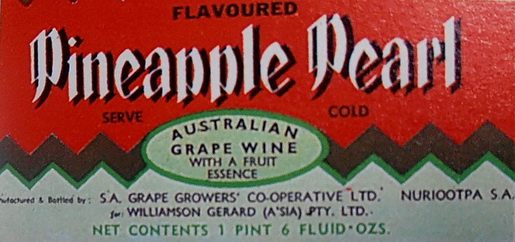

This coincided with new winemaking technologies in the form of pressure fermentation and refrigeration, which made a new style of fresh white wine possible. The Barons of the Barossa added some bubbles or retained some sugar (or both) to seduce more drinkers away from their sweet fortified staples. By now, it had become acceptable for women to drink wine (and smoke). Read more in The 1960s – from Pearl Wine to Chateau Cardboard.

An Early effort by Wolf Blass

The Path to Market

Sparkling Barossa Pearl, Hamilton’s Ewell Moselle and Lindemans Ben Ean Moselle were the wines at the head of the fifties revival. Great wines they were not, but they opened up the market. The next hurdle was the distribution system: there were no distributors, no wine writers, no wine books, no wine educators, no wine fares – all the things we take for granted these days.

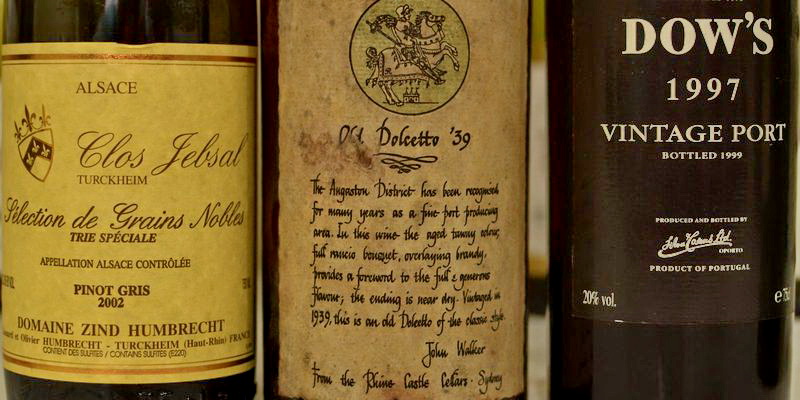

This was the gap filled by enterprising men like JK (Johnny) Walker, Harry Brown, Douglas Lamb, Doug Crittenden, Doug Seabrook, Dan Murphy and others. They were merchants (negociants in the true sense) who bought wine in bulk from the wineries and bottled them under their own labels (usually indicating the source), a longstanding tradition in France and the UK. They did much more than sell wine; they developed the market. They introduced wine drinkers to wines and their makers.

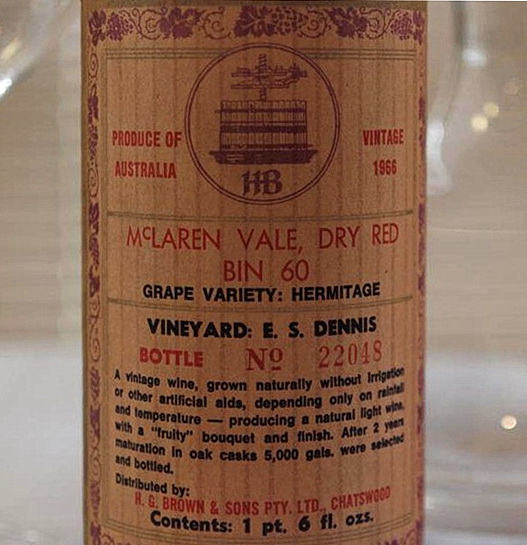

The merchants also created brands that became household names. Anyone remember Rhinecastle Bin 26A or HG Brown’s Bin 60?

JK Walker

The First Fifty Years of the Wine and Food Society of NSW by Joseph Glascott makes fascinating reading. ‘The late J.K.Walker Snr. developed an interest in wine in the 1920s as a hotelier in Woolloomooloo,’ Glascott tells us, ‘and later introduced Hunter River wine to the Melbourne market. His Rhine Castle Cellars in Pitt Street became the gathering place of woolbuyers, mainly French, after the auctions on the floor above.’

‘These men … were led there by Henri Renault, the only son of a food and wine-loving Lyons family. The wine and cheese-tasting meetings soon developed into more formalised luncheons. Johnnie Walker asked Henri and his wife Jeanne, who arrived from France in 1937, to help prepare lunches for the group on Tuesdays. Mrs Jeanne Renault remembers the Rhine Castle premises as “very beautiful with a genuine old cellar atmosphere.” It had “wonderful oak furniture and fittings”.’

David Sutherland Smith, of All Saints Vineyard near Rutherglen, learned about Andre Simon’s Wine and Food Society in London and founded a Wine and Food Society in Melbourne in 1937. J.K.Walker launched the Wine and Food Society of NSW in the Rhine Castle Cellars 2 years later. The founding members were J.K.Walker, Dr Gilbert Phillips, Maurice O’Shea, Henri Renault and Gilbert Graham.

A 1939 Dolcetto bottled by JK Walker was still with us at a recent dinner

A 1939 Dolcetto bottled by JK Walker was still with us at a recent dinner

The late Max Lake recalled the early days this way: ‘Well, Johnnie [Walker] took an eager group of us up. It was quite a trip actually. We went up in a train, and then bus to the Hunter, and we swanned around in Tullochs and Lindemans, Tyrrells, McWilliams, Elliotts, Draytons—at different times. And Johnnie often cooked. We tasted wine out of barrel, and we got to talk quite a bit about wine and share. He was just a marvellous man—Johnnie. He did it to sell wine. People often denigrated him but he enjoyed people. And everybody always enjoyed themselves when they went with him. Didn’t cost a lot of money.’

In 1957 JK established the Bistro restaurant in the Royal Exchange building in downtown Sydney, ‘with stone floors, Australia’s first public open kitchen, and the novelty of ordering from a blackboard menu and choosing wine from racks in the bar, it transformed Sydney business lunches–-‘’a glass of wine, a plate of spaghetti and back at work in an hour’’. Walker started the Angus Steak Cave in 1962, and Sydney’s CBD never looked back. More Here.

Harry Brown

In many ways, Harry Brown is the most interesting character of them all. He had more vision and more marketing nous than the rest. He started working for JK Walker at Rhinecastle wines in 1936 at the tender age of 18. In the fifties, Rhinecastle became a thriving business with wine sales taking off , and Harry soon showed he could read the market before it spoke to anyone else.

Harry saw the potential of wines like Houghton’s White Burgundy and McLaren Vale Shiraz early on. At one point, Rhinecastle sold more of Hardy’s wines than Hardy’s did under its own labels. Harry also saw the value of establishing fixed Bin numbers, which Rhinecastle had changed every year. Bin 26A red was the most famous example, almost becoming a cult wine in the early sixties.

H.G. Brown and Sons

JK Walker was so busy with the bistro and direct sales and the Wine Society that he sold the wholesale side to Harry in 1964, for 20,000 pounds. ‘The opening portfolio of H.G. Brown and Sons included Houghton’s, Browns of Milawa, Tullochs, Elliots and the Rhinecastle brands which included the very successful Bin 26A,’ David Farmer wrote in a recent piece on Harry Brown.

With the red wine boom unfolding, Harry saw the potential for a soft red at a time when most of our reds needed years to soften – so much for Wolf Blass’s claim that he came up with that idea several years later. This was the birth of Browns Bin 60 Hermitage and its distinctive wrapper printed on packing paper. The story goes that, at one point in the seventies, Bin 60 outsold both Jacob’s Creek and Tyrrell’s Long Flat reds.

The irony is that Harry Brown saw the potential of Wolfie’s soft reds as well and secured the agency for NSW. He did an enormous amount to put Wolfie on the map in NSW.

Wine Rationing?

Twenty years earlier, wine merchants couldn’t give table wine away. Now, the best wines were on allocation. I remember hunting around for the latest Wolf Blass red with a mate, and guys in bottle shops being very coy about reaching under the counter and handing a few bottles over – at full price. It was the same with Tulloch’s Private Bin Dry Red, which Harry Brown also made famous. Some Penfolds reds were on allocation as well.

All the while, Harry added more agencies to his portfolio: Brian Barry, All Saints, Quelltaler, Jim Ingolby, Kay Bros and the Stanley Wine Company. He seems to have seen the potential of McLaren Vale Shiraz decades before Robert Parker declared the stuff the next best thing since mother’s milk.

Marketing Nous

Harry also showed great business acumen in selecting the wines he imported, which included Mouton Rothschild, Trimbach, Laurent Perrier, Martell cognacs, Marie Brizard, Paul Bouchard Aine, Deinhard, Joseph Drouhin and Mommessin. Harry also secured the agency for Mateus Rosé, which sold 60,000 cases in 1979. David Farmer writes that, ‘at the time, Harry could only get 200 cases a month of Houghton’s rose.’

Houghton’s White Burgundy remained on allocation until the early eighties, and Harry was keen to promote Quelltaler White Burgundy to fill the void. He convinced Larry Sobels to show the vintage and medals won on the label, and sales went from 20 cases per month to 500. Another example David Farmer gives is that of Tulloch’s Riesling, which Harry repackaged in a Riesling bottle and doubled its sales.

Al Hill says Harry was pretty smart. He saw the booming restaurant trade, and came up with a neat way to turn most restaurateurs into loyal customers: he printed their wine lists. Seems like a simple thing but in the days before desktop publishing, wine lists were a pain. As soon as a wine or vintage year changed, the list had to be reprinted. Harry offered to take care of the problem and ended up supplying about three quarters of the restaurant market in NSW. The remaining quarter were bad payers, Al says, and Harry didn’t want them.

Harry saw big opportunities in the Pacific islands, selling wines to the burgeoning resort market in the late sixties. Al Hill travelled all around the Pacific from PNG to Fiji to Noumea. The next step was Europe – once again, Harry was ahead of the rest.

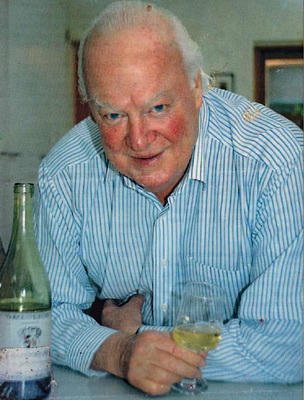

Harry is the man in the middle

Harry is the man in the middle

The Stanley Wine Company

Mick Knappstein was making terrific reds and whites in the seventies – Bin 49 Cabernet Sauvignon, Bin 56 Cabernet Malbec and Bin 5 and 7 Riesling – and these were often on allocation. However, over 80% of the wine Stanley made at the time was sold to other companies. In 1980, the family decided to sell the company to Heinz, where the bean counters had no time for fine wines and decided to go all out on cask wine.

They also wanted to control the distribution, which put Harry in a difficult position so he ended up selling H.G. Brown and Sons to Heinz. If he hadn’t done that, says David Farmer, he would’ve lost the Stanley agency. That may be so but why would Harry sell the whole business, given all the other irons he had in the fire? It may have had more to do with his younger son Robin’s sudden death at 32 years of age of heart failure following a squash game.

Harry spent his remaining years selling wine for Tyrrells, mostly to the restaurant clients he’d serviced for most of his life. Harry was Tyrrells’ top salesman, pulling in over a million dollars’ worth of sales a year. He died in 1999.

Doug Crittenden

Doug worked in his father’s grocery store in Malvern after WWII, where he developed an interest in table wine. He had to drive to South Australia to source wine direct from makers in the Barossa and McLaren Vales. ‘I had a great rapport with most of the wineries over there in South Australia,’ he told Max Allen in a recent interview. ‘In those days you practically knew everyone in the industry and what their wines were like. But they weren’t selling much table wine at all, and there were hardly any cellar doors.’

Doug Crittenden bought most of the wine in barrel and bottled and labelled it in the family’s cellars at Malvern. ‘We always told the customer where the wine was made,’ Doug made clear. ‘If the wine came from Reynella it was labelled as Reynella. If it came from Seaview it was labelled as Seaview.’

Doug was one of the first to taste the 1953 Orlando Riesling, which was made using pressure fermentation. He was so impressed he told Keith Gramp he’d take all he could get his hands on. He ended up selling ‘100 dozen of the wine before anybody had even tasted it,’ according to Max Allen. More Here.

Tom and Doug Seabrook

This family business goes back to 1878. Doug’s father Tom was one of the brave band of wine men who kept the faith during the temperance years. Tom was a teetotaller until the age of 32, but later became chairman of wine judges at the Royal Show in Melbourne. People said he had the best palate in the country and knew more about wine than anybody else.

Tom’s son Doug was also chairman of judges at the RMWS for many years. He was a passionate promoter of wine and educator of ordinary people. It’s easy to forget that these guys did everything, from buying wine in bulk, bottling and labelling it, promoting it, selling it and educating the punters.

Seabrook Wines is now run by Doug’s son Hamish who continues the tradition of sourcing fruit from the best wine growing areas across the country, and bottling it under the family label. More Here

Douglas Lamb

By all accounts, Doug led a charmed life. He spent time in England and France during and after the last World War. He studied law and was a barrister at the NSW bar before he ‘retired to the wine trade’ in 1951 as he called it. He bought a rundown Italian business with a wine licence and never looked back. He was another tireless promoter and educator, another conduit between wineries and a public thirsty for knowledge.

Doug was a respected wine judge, a Chevalier Du Tastevin Clos de Vougeot, and he won the Diplome d’Honneur Des Vignerons de Champagne. He also became a vocal supporter of Max Schubert’s Grange in the days when Penfolds had told Max to stop making the wine. Doug was a director and made the ‘petticoat government’ that ran Penfolds at the time give Max a free rein.

Dan Murphy

Daniel Francis Murphy learned the trade working in a liquor store owned by his father Timothy. Dan decided that he could do it better and set up a store a few hundred meters away. Dan bought in bulk and sourced many of his wines directly from overseas. He wrote stories and reviews about his wines, he held social functions and started a wine club. Dan Murphy’s formula for success was simple: offer the most extensive range at the lowest prices possible, and add plenty of enthusiasm.

Dan wrote several books, which were among the most boring wine books ever written IMHO, but there was never any doubt about his unwavering focus on quality wine. In 1985, Tony Leon joined Dan. It was clear that supermarket chains would soon begin to play a big role in wine retail, and Tony persuaded Dan Murphy to move to a high volume, heavy discount pricing model and the business boomed.

In 1988, Dan Murphy was charged with conspiring to defraud the tax commissioner of $2 million in sales tax and was sentenced to two and half years jail (he served only six months due to failing health). He was forced to repay the sales tax plus substantial fines. ‘Tony contends his mentor was given bad advice and the offences happened before he arrived,’ writes Winestate magazine, ‘ but he still mortgaged his house to help his boss. In return, Murphy offered him half of the business.’

In 1998, Dan Murphy’s had grown into a chain of 5 discount stores with an annual turnover of $100 million. Woolworths bought Dan’s and retained Tony Leon as general manager. When Tony left ten years later, Dan M had 86 stores Australia-wide with an annual turnover of $2 billion.

Kim