Or was it John Glaetzer who worked the miracles?

(It’s Wolfie’s 80th birthday this last week in August 2014, so we’ve updated the story)

Those backward colonials

Wolf Blass has had a big influence on Australian wine making and marketing, no question about that. There’s also no question that Wolf’s mouth and ego are way bigger than the body they’re attached to. Wolf simply loves to cast himself in the role of Maverick, the young German who showed those backward colonials how to make table wine. He also showed them how to make soft reds that were easy to enjoy at just a few years of age, and that was a smart move on his part.

How he worked this particular magic is an interesting question, since he’d never made a drop of red until he came to our shores. He briefly made bubbly for a German company using the Charmat method, and worked for Avery’s in Bristol for 2 years where he learned how to blend wines from Bordeaux and Burgundy into the house styles of the company. He was 25 years old when Ian Hickinbotham brought him out to make Perlwein for Kaiserstuhl in 1961.

Wolf to the Rescue

Wolf to the Rescue

When he was offered the job, Blass says he wanted to know what to expect in Australia, so he arranged a tasting in London with an Australian wine importer. He summed the experience up this way: ‘I tasted the wines and I scratched my head and said, ‘I don’t think I can do anything wrong – these wines are bloody awful.’

That statement fits well with Wolf’s story that he taught us how to make decent wine. Forget Max Schubert, Maurice O’Shea, Jack Mann, Ron Haselgrove, Roger Warren, Colin Preece and John Vickery – when you listen to Wolf in his radio interviews, these guys simply didn’t exist.

Ian Hickinbotham, a Roseworthy graduate of the fifties who made the first vintages for Wynns in Coonawarra in the early 1950s, says he hired Wolf because no Australian oenologist would take a job working for a co-operative winery in the early sixties. ‘Hick’ had been developing pearl wines for other wineries (Leo Buring among them) and he needed more winemakers. Hick grew Kaiserstuhl from a ramshackle outfit teetering on the brink to a successful business ten times it s size between 1957 and 1964.

The Boy Wonder

This is what a 1996 PR blurb says about Wolf’s early days: ‘With his talent in winemaking discovered, Wolf Blass received job offers in Australia and Venezuela. Fortunately for Australia he accepted a 3 year contract with Kaiser Stuhl Wines in Australia, and arrived in 1961. During these years he developed sparkling wines for Kaiser Stuhl, providing enormous competition for the then market leader, Orlando’s Barossa Pearl.’

This is pure fantasy. Wolf’s one contribution to the range of pearl wines Kaiserstuhl had already was Pineapple Pearl. More to the point, Wolf would’ve helped with the table wines as well and would’ve learned about the softening effects of malolactic fermentation and pH adjustment in red wines, because Hick was one of the first winemakers to embrace these techniques pioneered by his father Alan and Ray Beckwith at Penfolds.

How else do we explain that, by the mid sixties, Wolf was making red wine at Tolley Scott & Tolley, and acted as a consultant winemaker to Woodleys, Normans, Basedow and Bleasdale. Wolf gives no one credit for showing him the ropes, and we can only conclude that the Mouth of the Barossa was a genius.

They say he was a great blender but so were all of our great winemakers at the time. Blending was the common thing to do, viz the famous Mildara Cabernet Shiraz blends made by Ron Haselgrove, and the multi-regional blends made at Hardy’s by Roger Warren, the reds made by Colin Preece at Seppelt, and of course Grange and Bins 389 and 707 made by Max Schubert.

The Bat Cave

Whatever the facts, Wolf claims that he turned red winemaking in Australia upside down. ‘At the time our red wines were so heavy,’ Wolf told historians Rob Linn and June Edwards, ‘They didn’t know how to make them … they were selling the wine by telling the retailer, and the retailer told the consumer: you have to put the wine away, you wait for six/seven years and it’s alright to drink. And I thought that was lunatic … my idea was to get women to drink wine. And it had to be soft and smooth.’ Later on, he told the media: ‘My wines are sexy, they make weak men strong and strong women weak.’

So here is where the skill of blending came in, says Wolf, to make the wines more drinkable. He used new oak barrels to soften them, and that was uncommon in those days with the exception of Grange (Max Schubert used oak to achieve different effects). I suspect that Wolf also used more gentle methods in his handling of fruit, from crushing to fermenting, focusing on extracting soft fruit flavours rather than harsh grape or wood tannins. Most likely, he also experimented with micro-oxygenation.

No Wood, No Good

Wolf was no genius but he was pretty smart. He knew the importance oak played in red wine making, and he paid enormous attention to the casks in his winery. He used French Nevers, Tranquois and Limousin, American, Yugoslavian and German oak barrels, and understood the contribution of each type of oak on his wines. It’s not just choosing the right kinds of new barrels, but also deciding how long to store the wine in them, and how much of the wine should be matured in one-year or two-year-old barrels to avoid it tasting too oaky.

This is where Wolf had more Fingerspitzengefϋhl than most of his contemporaries. New oak maturation is a delicate process that requires constant checking and precise judgments as to the amount of time a particular wine should spend in each type of cask. There are no short cuts either in terms of time or money invested. New small oak barrels have long been an expensive commodity, and Wolf bought more of them than most winemakers. The barrels were used for four vintages and then sold.

Langhorne Creek

Blending certainly played a role, but so did fruit from Langhorne Creek, an area that’s been called ‘one of the best-kept secrets in Australian Viticulture.’ It lies about 50kms south-east of Adelaide, near the mouth of the Murray River and Lake Alexandrina, and the land is very fertile with deep alluvial loams. In the old days, the Bremer River was often diverted to flood-irrigate the vines on the fertile alluvial loams, but recent droughts and water restrictions upstream have put an end to that.

Today there are 6000 hectares under vine at Langhorne Creek, but in Wolf’s heyday it would’ve been less than 500. ‘When I got into this red wine, Langhorne Creek helped me,’ he told Rob Linn and June Edwards. ‘I loved the area. I didn’t like the South East. I still don’t like the South East and I stuck with Langhorne Creek and it’s become the second biggest grape growing district in Australia. So I must have been right in the first place.’

The fruit from this area is soft and plush at its best, but most of it was historically sold to bigger companies for blending. Stoneyfell Metala is one of the few wines here with a long history, and what a coincidence that it won the inaugural Jimmy Watson trophy in 1961, the same trophy Wolf would hold a mortgage on in the seventies?

I shared a bottle of 1967 Metala with friends over dinner in the late seventies, and we all preferred it to the 1966 Grange on the same table. I think it was Peter Lehmann at Saltram who made the wine at the time, and Peter was a very smart winemaker too. Langhorne Creek Cabernet was the backbone of Wolf’s grey label Cabernet Shiraz blends from the very beginning.

The Joker

When Wolf talked to Richard Fidler on ABC radio in 2011, he never mentioned Hick or Ron Haselgrove or Peter Lehmann or Max Schubert – more on Max’s groundbreaking work here – or any other winemakers and their work. When you search for that ABC interview on Google, this is what the entry in the search results says: ‘Wolf Blass has played a major role in transforming Australia into one of the world’s most respected winemaking countries.’

It was as if the German Genius had come to this backward land and civilised it all by himself. Everyone drank beer, he said. The red wines we made were no good. He talked about his many achievements, about how smart a winemaker he was, and about his marketing genius. He didn’t talk about anyone else, except Leo Buring and John Glaetzer.

Gentle John

John Glaetzer had worked with Wolf Blass after graduating from Roseworthy in 1970, and Wolf made him his chief winemaker in 1974. John made the wines that won Wolf three successive Jimmy Watsons in 1974, 1975 and 1976 (and a fourth in 1999). He also made the wines that won 11 Montgomery Trophies over the years for the best red at the Royal Adelaide Wine Show.

Lucky for Blass, John Glaetzer is the silent complement to Wolf’s noisy self-promoter. I bet you haven’t seen him on TV or heard him on the radio or seen him quoted in print. I can’t even find a decent photo of him on the net. John made his own wine, John’s Blend, for almost as long as he made wines for Wolf. His latest venture is Gipsie Jack (with Ben Potts of Bleasdale), and the website tells us that ‘John has always had a strong affinity with Langhorne Creek, long singing the praises of the exceptional quality fruit continually produced there.’

The real boy wonder

So Wolf had someone showing him the ropes after all, and a lot more besides.When I shared this discovery with some friends in the wine business, they frowned or chuckled and rolled their eyes as you might do when someone tells you they’ve discovered that the earth isn’t flat. Everybody Knows, as the Leonard Cohen song goes.

Digging extra deep, I found a wonderful story about John Glaetzer here, written by Ric Einstein (also known as TORB). Ric describes a special wine dinner he attended in Berrima with John as special guest in 2007. He says John was a man of few words and, ‘when he occasionally did speak, it sounded like he was mumbling underwater.’

And there’s a point in the story where we come right back to Hick and the importance of pH: Ric writes, ‘I bailed him up with a question: “These are big, oaky, ripe wines but there is absolutely no sense of flabbiness about them, in fact the acid, even the 99 is noticeably very fresh, how do you manage to achieve this?’ His initial response was succinct and to the point. ‘If you don’t get the pH right on day one you are screwed.’

John said he started thinking about how to adjust the pH even before the grapes hit the crusher. This is a great story that segues into an interview and more anecdotes. At one point Ric talks about Wolf testing John’s palate after he won a scholarship to Roseworthy. John was still in the agriculture course that preceded the winemaking course, but was working part-time at Normans winery. It was then that Wolf Blass decided to test him (he consulted to Normans and must’ve seen some talent in John.)

‘In a tasting room,’ the story goes, ‘Wolf lined up seventeen glasses of wine and told John to wade his way through them, and pick out the top three wines in order … After an hour of mucking around tasting the wines, Wolf got quite impatient with John and told him to stop stuffing around. John then picked out the wines he thought should be first, second and third, and proceeded to tell Wolf why he thought they deserved those positions.’

According to John, “The shit hit the fan. Wolfie accused me of looking at his notes. He was jumping up and down having a German tantrum, but it was impossible for me to have read his notes, because they were folded up in his back pocket. He couldn’t believe that I had picked the same three as him, in the same order. On that day he demanded that, as soon as I graduated, I was to work for him.”

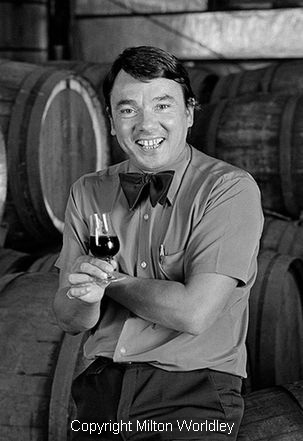

Wolf in marketing mode

Australia’s most decorated winemaker

John Glaetzer retired in 2004, after 3 decades of making wine for the Wolf Blass label. Even now, he’s happy to let others do the talking (and take the credit, it seems).

‘It is hard to know where to start when recounting John’s remarkable career,’ said Chris Hatcher who took over as Chief Winemaker for the Blass label (now owned by TWE), ‘the countless winemaking accolades or the hundreds of show judging appearances … John has been responsible for the creation of the hugely popular Yellow Label, the multiple award-winning Black Label, the continuing evolution of the Wolf Blass style, and the creation of the President’s Selection for international markets.’

‘John makes wines that people want to drink,’ Chris added. ‘He makes wines with softness and richness of flavour and famously matures his wines in the very best oak barrels. Among Australian winemaking circles, John is renowned as the man who coined the famous phrase No wood: no good.’

All in all, John Glaetzer has collected 3,600 awards, trophies and medals in his winemaking career so far, and few people in Australia have ever heard of him.

The real Wolf

I’m not trying to drag down Wolf’s achievements, I just want to add the big pieces he leaves out of his success story. John Glaetzer was a mighty big piece of his success, no question, but it was Wolf who added the untiring drive to make his enterprise a commercial success.

Wolf wasn’t the first to use small new oak for maturing his reds but, where Max Schubert used oak to extract more tannins to give Grange more authority and longevity, Wolf used it to soften his reds. Many said his reds wouldn’t last the distance, but they were wrong: some of Wolf’s wines of the sixties and seventies are still in good shape.

Max Schubert once paid Wolf this tribute: ‘Wolf Blass can look at the grapes and picture what he’ll do with them. You have to conceive wine out in the vineyard. Wolf is one of the rare people with this imagination.’ Max Schubert freely gave credit to others, and Wolf should take a big leaf out of his book.

Kim

More reading